The Lights Are Still Off: What COP30’s Promises Mean for the African Child

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....

I grew up learning how to adapt to electricity failure. You learn early what time power usually goes out, you know when to charge phones, when to pump water, and when to run appliances. You learn the...

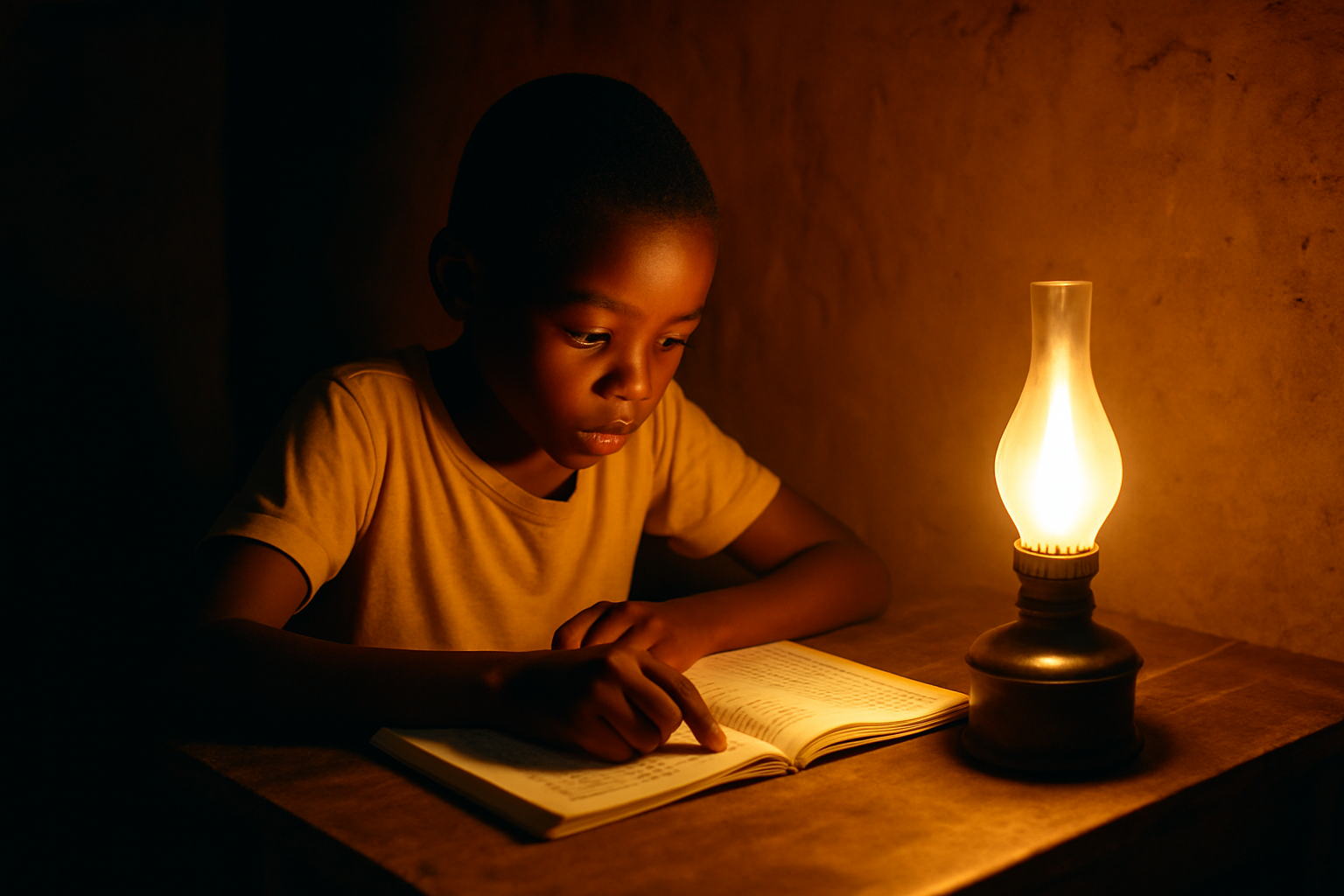

When negotiators at COP30 announced new climate-finance commitments in Belém, my mind went to the children I met earlier this year in a village outside Makurdi, Nigeria, six boys and girls bent over their schoolbooks under a single kerosene lamp, eyes squinting in the dim yellow burn. You could hear the buzzing of insects, the flick of pages, and the quiet rhythm of children trying to learn in darkness that should no longer exist.

These are the children COP30 was supposed to help.

These are the children who still wait.

In climate conferences, we talk in billions; USD 300 billion by 2035, tripled adaptation finance, fossil-fuel transition pathways, and voluntary roadmaps, etc. But for the African child, the real question is simple:

“Will this bring light to my home?”

So far, the answer is still uncertain.

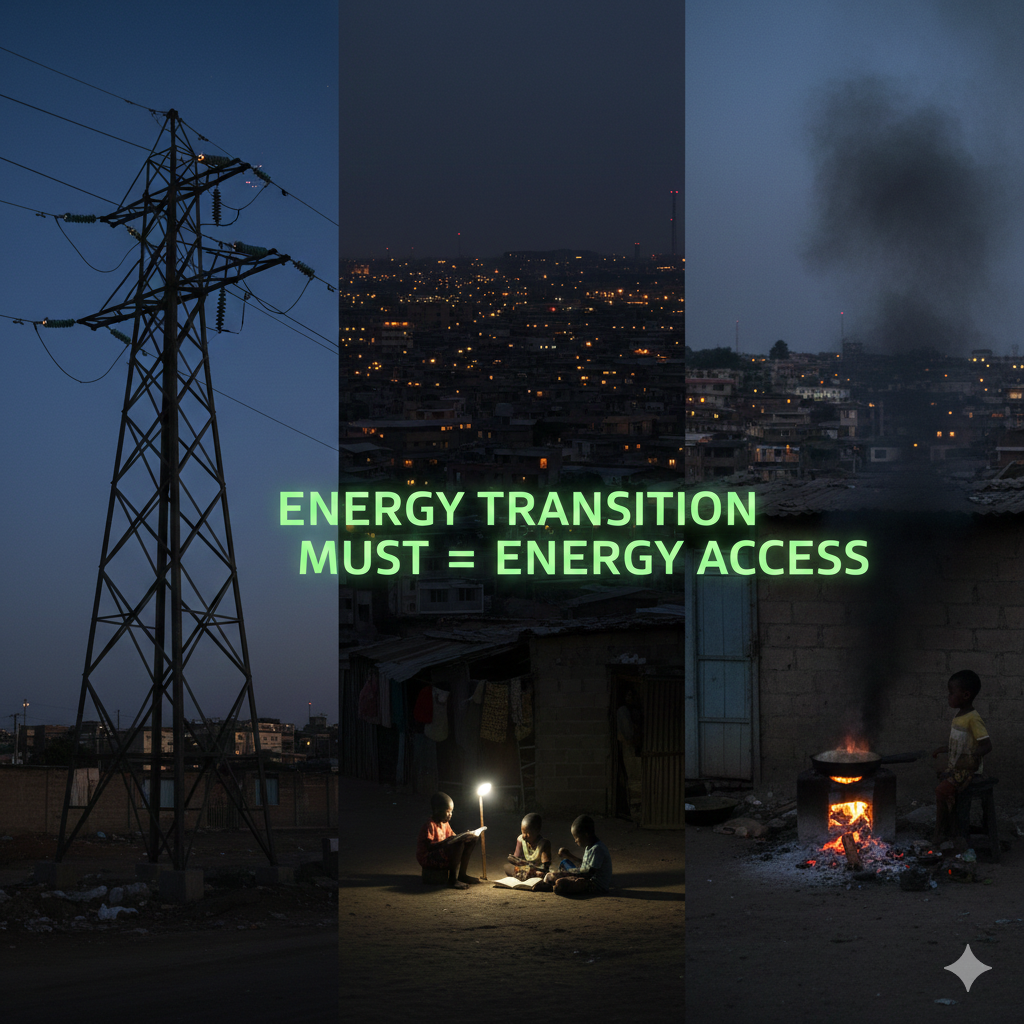

COP30 gave the world many declarations, roadmaps and finance projections, but very few binding obligations. For Africa, where 600 million people still lack electricity, and nearly one billion depend on firewood or charcoal for cooking, ambiguity is a burden.

The new financing pledges sound historic. On paper, they are. But Africa has seen commitments before: the USD 100 billion pledge from Copenhagen, the Paris Agreement’s adaptation goals, and the Glasgow pledges to triple access investment. Some were delayed. Most never arrived. Others were reallocated or rebranded.

This is the gap between political ambition and practical delivery, and African children grow up inside that gap.

At COP30, leaders agreed to triple adaptation finance by 2035. They reaffirmed a USD 300 billion-per-year climate finance track. They endorsed a new Global Goal on Adaptation with 59 indicators. They launched new partnerships for clean electricity access, grid expansion, and clean cooking in schools.

These are good signals.

But signals do not light classrooms.

They do not power clinics.

They do not reduce the 2.5 million annual deaths from household air pollution.

Children cannot study on declarations.

Whenever Africa debates energy, children are almost invisible in the conversation. We focus on megawatts, investment flows, transmission lines, and minerals. Yet children live the consequences of a failed transition more directly than anyone else.

They inhale the smoke of firewood kitchens.

They learn in overheated, unventilated classrooms.

They drink unsafe water when pumps fail.

They miss school during floods and heatwaves.

They sleep without cooling during lethal heat nights.

They watch communities uprooted by drought or storms.

Energy is not a sector.

It is the foundation of childhood.

This is why COP30 matters: not because leaders signed documents, but because the outcomes will decide whether a generation of African children grows up with dignity or deprivation.

For the first time in years, COP30 explicitly recognised universal electricity access and clean cooking as central to the climate agenda. Initiatives like the UN Electricity Access Plan (2035) and the Clean Cooking in Schools platform offer real entry points for African governments to demand support.

But these platforms are voluntary.

There is no guaranteed funding.

Timelines stretch far beyond the urgency children live with every day.

The absence of a binding fossil fuel phase-out, replaced with voluntary transition pathways, is not an abstract diplomatic flaw. It is a future written in heatwaves, floods, crop failures, and hunger.

Every year of delay worsens the climate shocks African children inherit.

Tripling adaptation finance by 2035 is too distant for communities already hit by climate disasters. Many African governments need adaptation financing now, not in a decade. Children living through today’s extreme heat cannot wait for 2035.

A framework for just transition is welcome. But without finance, it is a moral statement, not a structural tool. For children in coal towns, oil regions and mining communities, justice delayed is childhood denied.

The African child’s life is shaped by one simple fact:

Electricity determines opportunity.

A child with light can study.

A child with power can cool a room during heatwaves.

A child with a fridge can enjoy safe food and medicine.

A child with connected parents gains economic stability.

A child with a powered clinic at birth enters the world safer.

Yet millions of African children grow up in darkness.

Darkness is not neutral.

Darkness is a curriculum, one that teaches limitation.

When COP30 leaders speak of numbers and targets, I hear those children flipping pages under a dim flame, their futures narrowing with every hour without power.

We cannot wait for the world’s pace.

Africa must negotiate, plan and act with clarity.

Universal electricity access should not be framed as development; it is dignity.

We must climate-proof our grids, decentralise power systems and scale mini-grids.

School feeding programmes, clinics, and rural communities must be the first beneficiaries.

We cannot export cobalt to power the world while our children live without light.

Domestic capital, pensions, sovereign funds, and diaspora bonds must complement global finance.

The energy transition is not about carbon alone.

It is about children, their futures, their health, their safety, their hope.

When I think of COP30, I don’t see podiums or pledges.

I see the six children under the kerosene lamp.

I see their eyes half-lit by flame, half-lost in shadow.

I see childhoods that could be filled with light, technology, and creativity, held back by a problem the world already knows how to solve.

If COP30 is to mean anything, it must mean this:

No African child should grow up in the dark.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

For most of the past decade, climate finance has been discussed as a moral equation. If African countries showed ambition, net-zero targets, transition plans, long lists of renewable projects, and...