Climate Finance Is No Longer About Promises, It’s About Power Systems

For more than a decade, the global energy transition has been sold as a story of technology. We are told solar panels are getting cheaper, wind turbines are getting taller, and batteries are...

For most of modern economic history, electricity demand has followed growth. When economies expanded, electricity use rose steadily and predictably, rarely faster. That relationship is now breaking....

For most of the past decade, climate finance has been discussed as a moral equation.

If African countries showed ambition, net-zero targets, transition plans, long lists of renewable projects, and finance would follow. Promises would unlock pledges, and pledges would unlock capital. That era is ending.

I have sat in rooms where African ministers spoke passionately about climate vulnerability, historical injustice, and development needs, only to leave without firm financing commitments. I have also watched countries with fewer speeches, fewer press releases, and less rhetorical ambition secure capital. The difference was in systems and not morality.

Today, climate finance is flowing less to those who promise the most, and more to those who can deliver electrons, collect revenue, honour contracts, and manage political risk. In other words, to countries whose power systems work, or are being credibly fixed.

Three recent developments make this shift impossible to ignore.

In January 2026, the United States formally withdrew from the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), raising legal and diplomatic questions about the future of global climate cooperation.

Regardless of one’s view of the decision, the signal is clear: multilateral climate finance is becoming less predictable. Pooled funds, collective enforcement, and shared rules are weakening. And capital is adapting accordingly.

Around the same time, Ghana announced it had cleared $1.47 billion in energy-sector arrears, a move that immediately improved investor confidence in its power sector.

There was no grand climate summit announcement, no rhetoric, just a balance-sheet decision. That decision mattered more to financiers than any speech.

Nigeria, long associated with grid instability and policy inconsistency, announced a $2 billion climate and energy transition fund, signalling a shift toward structured, domestically anchored transition finance.

The fund alone will not fix Nigeria’s power sector. But the signal that transition finance must be institutionalised, not improvised, was unmistakable.

African countries aren't short of ambition, net-zero pledges, nationally determined contributions, energy transition plans, hydrogen strategies, or minerals roadmaps.

What they are often short of is delivery credibility. From the perspective of financiers, ambition without systems creates three risks:

If these questions cannot be answered convincingly, finance stalls, no matter how compelling the climate narrative. This isn't cynicism. It is risk management.

I grew up in a country where power cuts were normalised. Where generators were considered a basic household asset, and businesses learned to survive despite the grid, not because of it.

That lived experience matters. Because from the outside, a grid collapse is a credibility signal. Every time a national grid fails:

Grid instability tells financiers something uncomfortable: that new renewable capacity may be stranded, curtailed, or unpaid for.

The global clean-energy transition is no longer constrained by technology. Solar, wind, batteries, and grid management tools are proven and falling in cost. The International Energy Agency has repeatedly shown that renewables dominate new power additions globally.

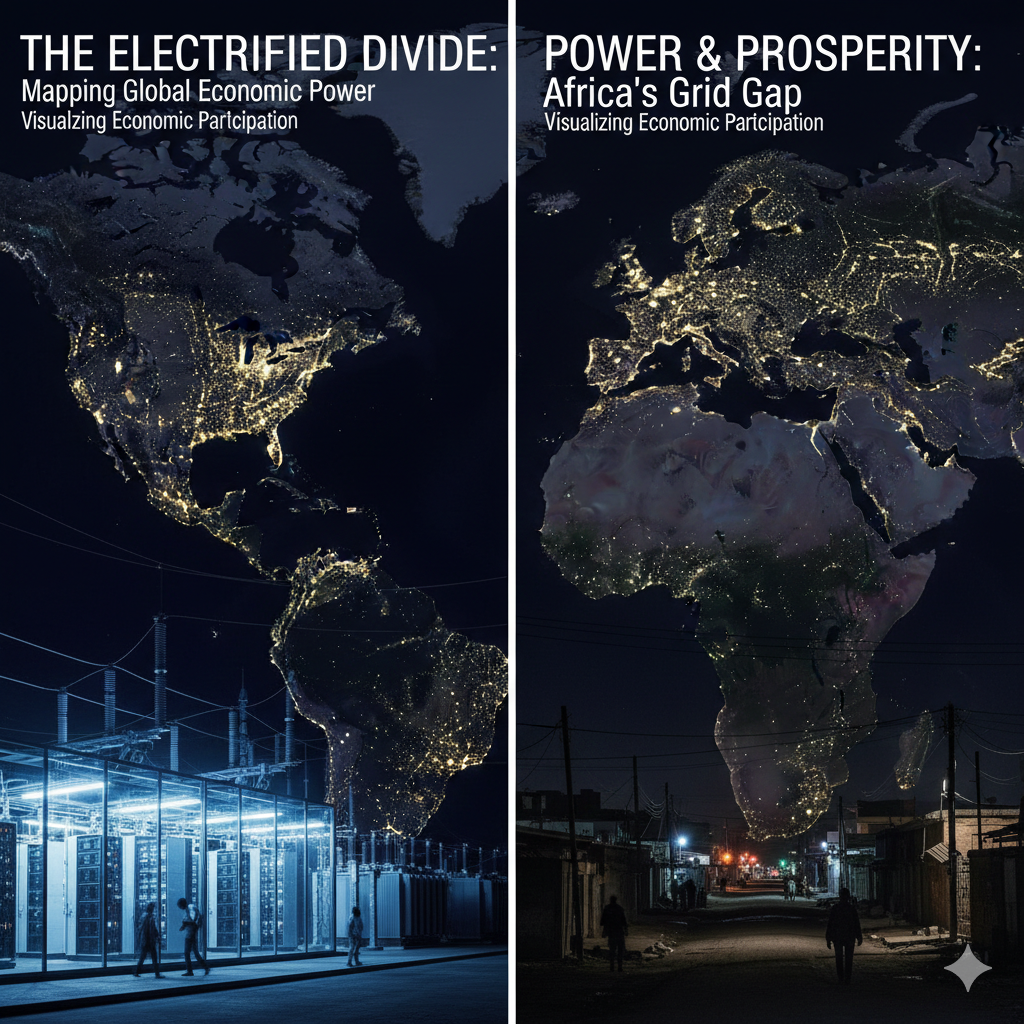

Africa’s constraint is systemic.

These are power-system problems. And climate finance increasingly follows the logic of power systems.

Bankable transition readiness is about trajectory, and not merely projection. Financiers look for five signals.

This means:

Ghana’s arrears clearance mattered because it showed political willingness to confront hard truths.

Countries that acknowledge grid limits and invest in reinforcement, dispatch reform, and flexibility are taken more seriously than those that publish capacity targets without system plans.

Who bears currency risk? Who guarantees offtake? What happens if politics changes? These questions must be answered in contracts, not press releases.

Countries that mobilise pension funds, banks, or local-currency instruments signal seriousness. They show they have “skin in the game”.

Kenya’s move toward sustainability-linked borrowing and green taxonomies is one example of this direction of travel.

Perhaps the hardest to quantify, but the most decisive. Do governments stick to reforms when they become unpopular? Do they protect regulators? Do they honour contracts across electoral cycles? Finance follows discipline.

This shift unsettles many advocates, and rightly so. Climate finance was supposed to be about solidarity, justice. and shared responsibility. But as global politics hardens, finance is becoming transactional:

While this isn't ideal, it is the reality. The danger for Africa is not recognising this shift too late.

The implication isn't that Africa should abandon moral arguments. Those remain valid, but they must be matched with system-building. Climate ambition must now be expressed through:

In this new era, a functioning grid is a climate asset.

Climate finance is no longer a reward for good intentions, but a response to credible performance pathways.

The countries that will attract transition finance in the next decade will be those that can demonstrate persistently that their power systems are becoming more reliable, more transparent, and more bankable.

For Africa, this is a hard truth, but also an opportunity. Because while promises are easy to copy, systems are not.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

As Mining Indaba opens in a few days, one point of alignment is already clear: value addition has become the dominant political language around Africa’s future in critical minerals. From policy...