Adaptation Is Becoming Africa’s Energy Trap

For more than a decade, the global energy transition has been sold as a story of technology. We are told solar panels are getting cheaper, wind turbines are getting taller, and batteries are...

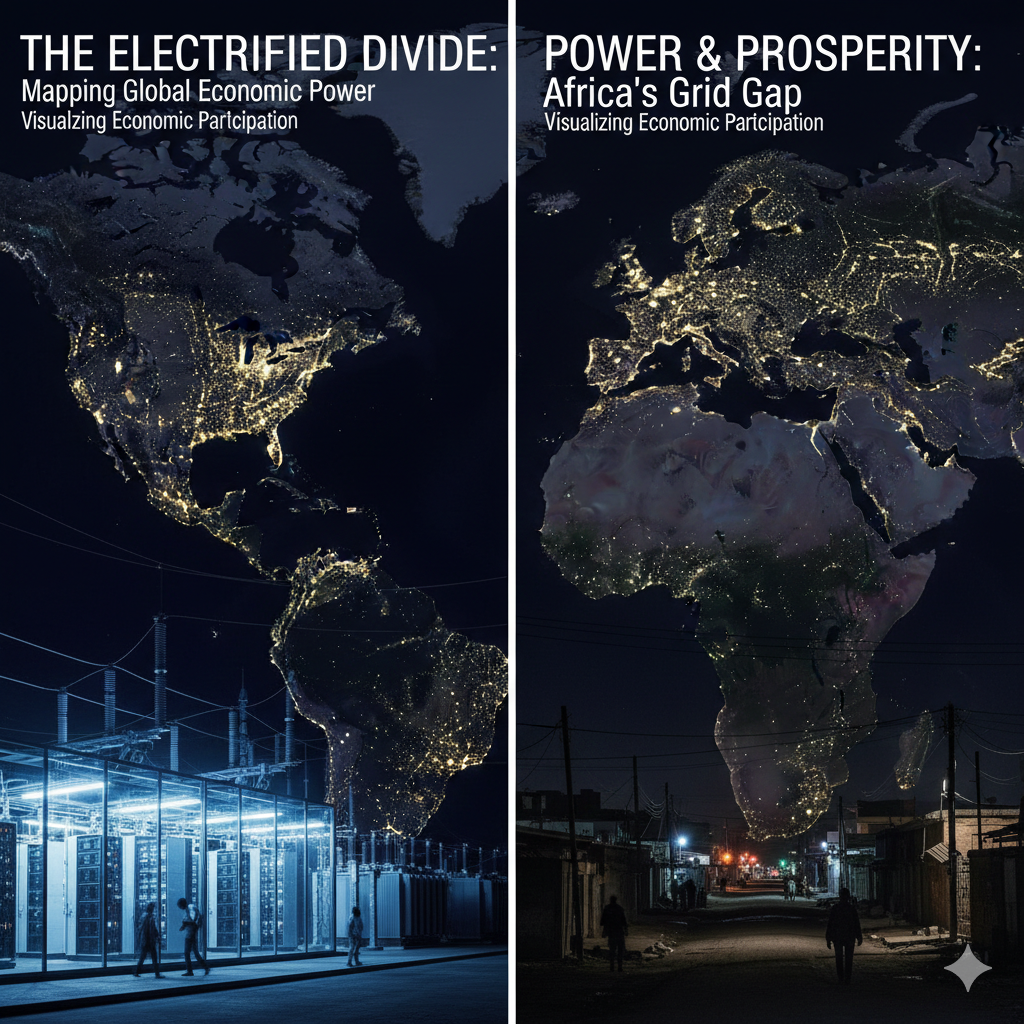

For most of modern economic history, electricity demand has followed growth. When economies expanded, electricity use rose steadily and predictably, rarely faster. That relationship is now breaking....

I grew up learning how to adapt to electricity failure. You learn early what time power usually goes out, you know when to charge phones, when to pump water, and when to run appliances. You learn the sound of generators, the smell of diesel, and the rhythm of darkness. You simply adjust your life around it.

For years, this ability to adapt has been framed as African resilience, a strength and proof of ingenuity in the face of scarcity. But there is a moment when resilience stops being admirable and starts becoming dangerous.

I believe Africa has crossed that line. Our celebrated ability to cope with energy failure through generators, informal connections, solar workarounds, candles and compromises is no longer a bridge to progress. It has become a trap. One that entrenches grid failure, delays reform, and weakens the very case Africa makes for serious transition finance.

Earlier this year, I wrote about Africa’s energy paradox: a continent that powers the global clean-tech transition with minerals while living in the dark. That piece made a moral claim. This one makes a harder argument: adaptation itself is now part of the problem, because when societies adapt too well to breakdown, breakdown stops feeling exceptional. And when failure becomes normal, it stops triggering reform.

What we have failed to interrogate is this: at what point does resilience stop being strength and start becoming an alibi for neglect?

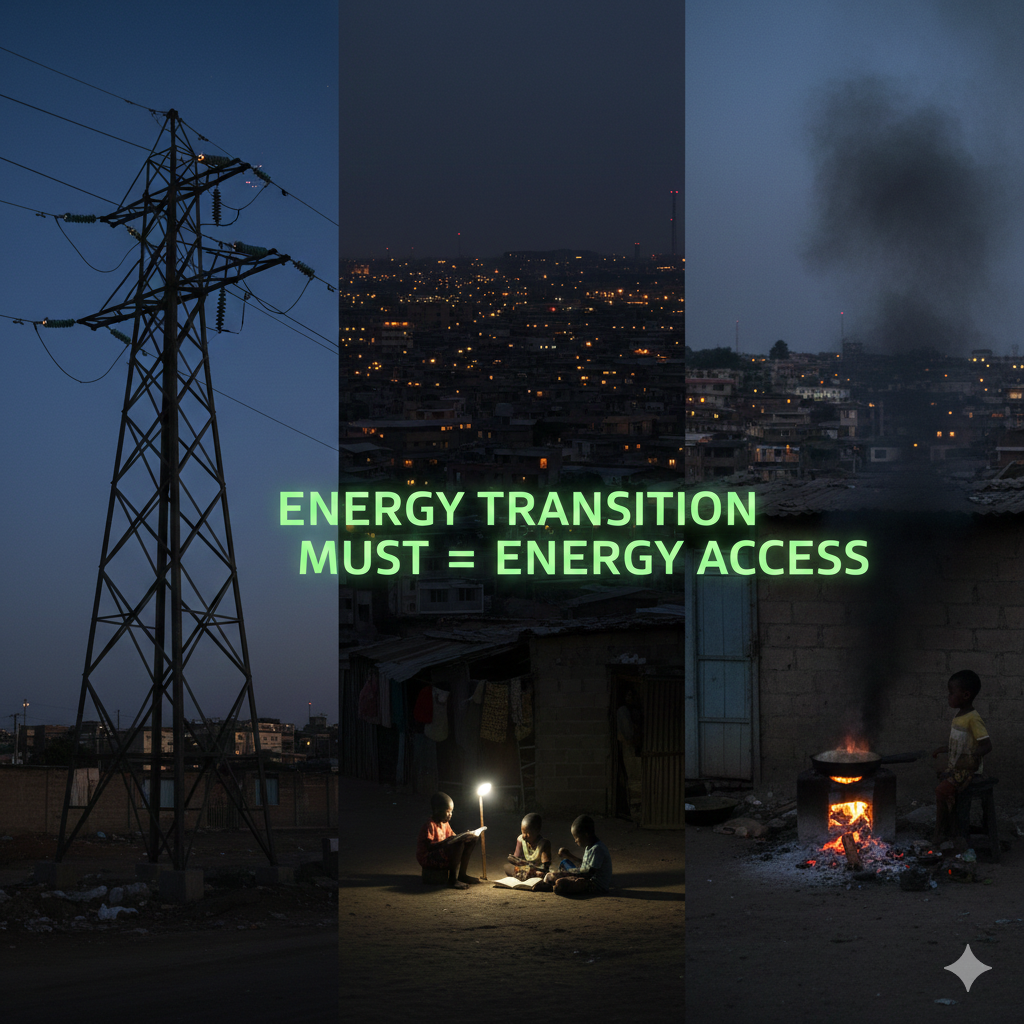

Adaptation is indispensable in the face of climate shocks. Droughts, floods, heatwaves, etc., are episodic disruptions, and coping mechanisms save lives.

But energy is different. Electricity isn't a shock. It is a system. And systems do not improve through adaptation alone; they improve through pressure, accountability, and investment.

In much of Africa, that pressure has been diffused. When grids collapse, life continues, imperfectly, expensively, unjustly, but it continues. Middle-class households buy generators or solar systems, businesses factor diesel into operating costs, hospitals improvise, and informal solutions fill the gap.

And because society absorbs the pain privately, the system escapes responsibility publicly. Failure becomes survivable, and survivable failure is tolerated failure. This is the trap.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Nigeria.

Some weeks ago, the national grid collapsed again, leaving millions without power. Government officials explained the technical causes, the public reacted with frustration, but also with resignation and life simply continued.

What struck me was not the collapse itself, but the reaction. There was outrage, yes, but also resignation. A sense that this is simply how things are, that Nigerians are used to it.

That normalisation is corrosive. Because when a country of more than 200 million people can lose its grid and still function, through generators, private solar, and informal coping, the incentive for deep structural reform weakens. Grid collapse stops being a national emergency and becomes a background inconvenience.

Policy failure becomes a routine, and routinised failure rarely gets fixed.

From the perspective of governments and financiers, adaptation sends three dangerous signals.

If households and businesses self-provide power, grid failure no longer produces an immediate political crisis. The pressure to prioritise transmission, distribution losses, tariff reform, and utility governance diminishes.

Diesel generators impose enormous costs, financial, health, and environmental, but these costs are borne privately. They do not appear clearly in public balance sheets.

Nigeria, for example, spends billions annually on self-generation. Yet this rarely enters energy planning discussions as a systemic loss.

When everyone improvises, it becomes harder to assign responsibility. Who failed, the utility, the ministry, the regulator, or “the system”? Adaptation fragments accountability.

Solar has rightly been celebrated as a game-changer for Africa. And in many contexts, decentralised energy is essential. But there is a growing confusion between complementary solutions and substitutes for system reform.

Across many countries, informal solar installations, unregulated mini-grids, and off-grid workarounds are filling gaps left by failing utilities. But when these solutions operate outside national planning frameworks, they create a parallel energy economy, one that:

Decentralised energy should support system recovery, not become a substitute for it. When off-grid solutions replace the grid by default, the grid dies.

Ghana offers a revealing counterpoint. In January 2026, the government cleared $1.47 billion in energy-sector arrears, restoring confidence in the power sector’s financial credibility.

This was a confrontation of the problem and not an adaptation. Clearing arrears required fiscal sacrifice, political risk, and difficult negotiations. But it sent a clear signal: system failure would not simply be absorbed by citizens and businesses.

That is the difference between resilience and reform. One endures failure, and the other insists on fixing it.

Adaptation isn't neutral. Those who can afford generators, batteries, or solar systems cope. Those who cannot, women running informal businesses, small clinics, public schools, and rural households, bear the highest costs.

Energy adaptation privatises survival. It shifts electricity from a public good to a personal responsibility, and in doing so, it erodes the social contract that underpins public investment in grids, utilities, and national systems. The result is a two-tier energy reality: one private, one precarious.

Perhaps the most damaging effect of adaptation is psychological. When societies repeatedly adjust to failure, they adjust their expectations.

Power for a few hours a day becomes acceptable. Generator noise becomes normal, and darkness becomes routine. And once expectations fall, ambition follows.

This is how energy poverty becomes entrenched, not through lack of technology or capital, but through the erosion of insistence.

Systems rarely improve when failure is tolerated; they do when failure becomes politically unacceptable. That is the shift Africa now needs to make.

Breaking the adaptation trap doesn't mean abandoning decentralised solutions or resilience strategies. Africa will continue to need solar, mini-grids, backup systems, and coping mechanisms in the near term.

But it does require something more difficult: re-politicising system failure. For too long, power failure has been treated as a technical inconvenience rather than a political failure. The result is a culture of endurance instead of insistence.

Three shifts are essential.

One reason adaptation persists is that its costs are largely invisible.

Generators hum in backyards and in businesses and hospital compounds, but their true price, fuel imports, health impacts, lost productivity, emissions, and foregone investment, rarely appear in public accounts. Power outages disrupt lives daily, yet their economic cost is seldom quantified or debated at the highest political levels.

Governments must make these costs explicit. They should measure and publicly report:

What remains hidden can't be reformed, and what isn't politically visible is rarely prioritised.

There is a growing tendency, often well-intentioned, to speak of national grids as outdated or optional in Africa’s transition. This is a mistake, because grids aren't relics of a centralised past. They are the backbone of modern economies: enabling industrialisation, powering hospitals and water systems, supporting digital infrastructure, and allowing energy to be delivered at scale and at lower long-run cost.

Treating the grid as optional undermines both development and credibility. Countries that allow their grids to wither while celebrating workarounds send a damaging signal to investors and financiers: that system performance is secondary to improvisation. In a post-multilateral climate economy, that signal is costly. Decentralised energy should complement and strengthen grids, not replace them by default.

The most important shift is conceptual. Adaptation should no longer be an end in itself; it should be explicitly tied to system recovery.

This means:

In other words, coping mechanisms must be designed to buy time for reform, not to excuse its absence. Adaptation that floats freely, disconnected from reform, becomes permanent improvisation.

Resilience is supposed to be a bridge, not a destination. Africa’s ability to adapt has helped millions survive in the face of system failure. But survival isn't the same as progress, and coping isn't accountability.

If adaptation continues to replace reform, Africa risks locking itself into a low-expectation energy future, one where grids fail, systems stagnate, and serious transition finance looks elsewhere.

The lights will not stay on because people adapt better; they will, when adaptation gives way to insistence on systems that work, institutions that deliver, and accountability that doesn't fade when the generators start humming again. This path may be harder, but it leads forward.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....