Africa’s Electricity Access Targets Are Failing: Here’s the Blueprint to Fix Them

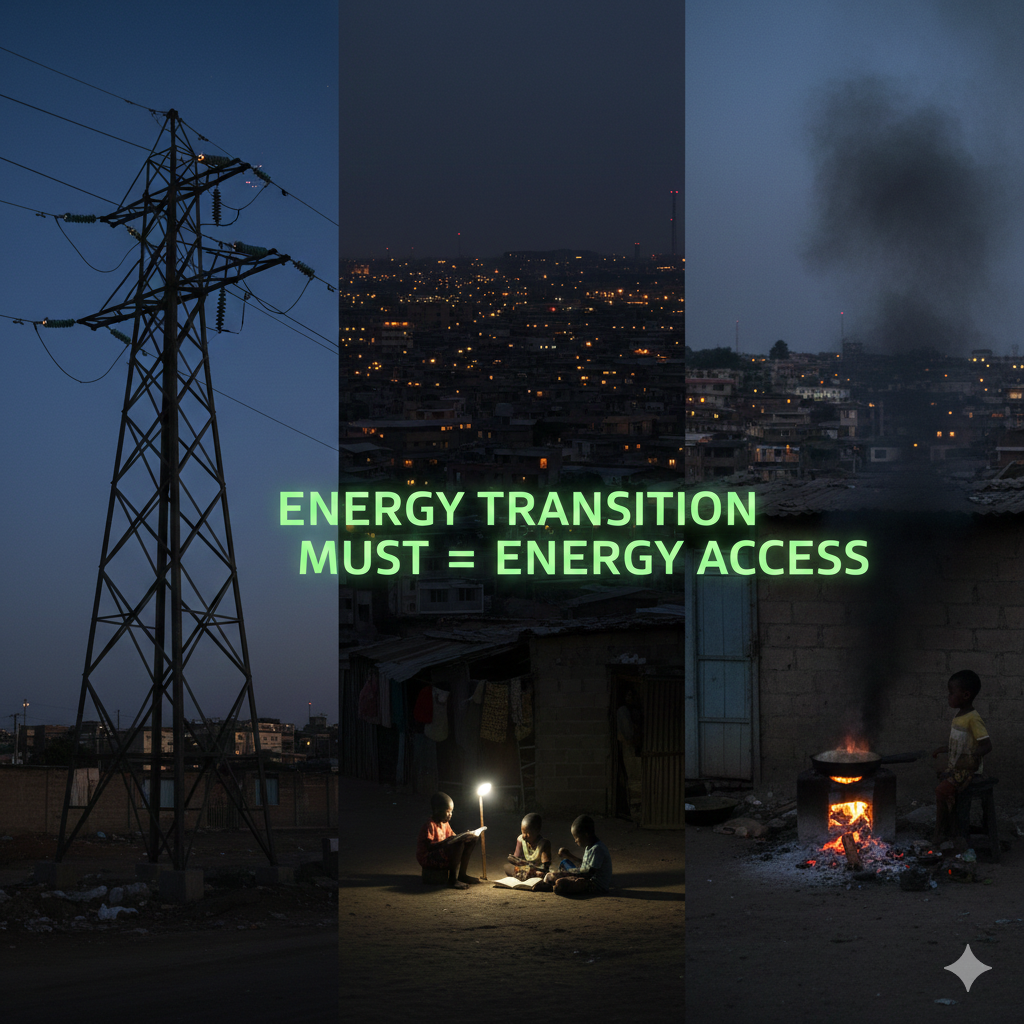

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....

I grew up learning how to adapt to electricity failure. You learn early what time power usually goes out, you know when to charge phones, when to pump water, and when to run appliances. You learn the...

There is a sentence repeated in nearly every African energy policy document: “universal access by 2030.” It is optimistic, visionary and mathematically impossible.

With just five years to go, Africa is nowhere near achieving universal electricity access. Indeed, the continent is off-track by decades. According to the latest International Energy Agency (IEA) projections, Africa will not reach universal access until well after 2060 if current trends continue, delaying opportunity, productivity and public health outcomes for generations.

The numbers are stark. But the human consequences are even starker.

Today, 600 million Africans still lack electricity. At least 350 million more receive power that is unreliable, rationed or available only for a few hours each day. Lights flicker, appliances burn out, machines stall, and clinics operate in the shadows.

These failures are not technical glitches. They are symptoms of deeper structural problems:

Access targets fail because the system designed to deliver them is fundamentally broken. A wire connected to a home that receives two hours of power per day is not electricity access, it is electrification theatre.

African policymakers are not blind to these challenges. Many have rolled out ambitious electrification plans. Yet progress has been slower than anticipated for three core reasons.

National grids across the continent are buckling under demand; they were never designed to handle. Transmission losses exceed 17% on average, and in some countries surpass 25%, among the highest in the world.

Even when new generation capacity comes online, it often cannot reach the communities that need it.

Electrification plans overwhelmingly depend on grid extension, even though:

Grid-first strategies are grid-only strategies by another name.

Most African utilities operate at a loss. Tariffs are politically suppressed, billing systems leak revenue, and subsidised diesel generation drains national budgets. In many cases, utilities cannot maintain existing infrastructure, let alone build new assets.

An insolvent utility cannot reliably expand access.

A utility without financial reform becomes an obstacle, not a delivery mechanism.

Solar home systems, mini-grids and productive-use energy appliances are not “alternative” solutions; they are the fastest path to universal access. Yet regulatory barriers, inconsistent subsidies and unclear licensing requirements hinder expansion.

The irony is profound: the technologies most capable of delivering electricity quickly are the least supported.

Africa does not have an electrification challenge.

It has an electrification strategy challenge.

Targets fail for predictable and preventable reasons:

1. They assume linear progress in a system that behaves non-linearly.

Adding 1 million new connections today is not equivalent to adding 1 million in 2030 when networks face far higher stress.

2. They underestimate financing gaps.

The IEA estimates Africa needs $25 billion per year to reach universal access. Actual flows remain below $6 billion, and most funding targets generation, not last-mile delivery.

3. They ignore poverty traps.

Connection fees, appliance costs and energy tariffs remain unaffordable for millions.

4. They treat access as a binary, not a spectrum.

Having a lightbulb does not mean having electricity that powers opportunity.

5. They are rarely tied to governance reform.

Electrification is as much a governance project as an engineering one.

The continent needs a shift from aspirational targets to actionable strategy, from megawatts to meaningful access, from symbolism to system redesign.

Below is a realistic blueprint.

Governments must measure:

Reliability metrics must become the new political scorecard.

Mini-grids can deliver Tier-4 power levels, enough for businesses, clinics and schools at a fraction of the cost and time of grid extension.

Scaling them requires:

Mini-grids are not a rural consolation prize. They are nation-building infrastructure.

This must include:

Utilities cannot deliver modern electricity while operating as political tools.

This is morally non-negotiable and financially feasible.

Electrifying every clinic and school would cost less than 0.1% of Africa’s annual GDP and deliver disproportionate gains in human development.

This is the most impactful “electrification dividend” Africa can unlock within five years.

Access becomes meaningful only when it powers incomes.

Governments should invest in:

Electricity must become a force multiplier for livelihoods.

Electricity is not simply a development input.

It determines:

Africa cannot industrialise in the dark; it can't educate in the dark, and it can't heal in the dark.

Universal access is not only an infrastructure milestone, it is a human rights milestone.

Africa’s electricity access crisis is solvable. What has been missing is alignment.

The continent must move from:

The path is clear. The tools exist and the urgency is undeniable.

Africa does not need more targets, what is needed is a blueprint that works.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

Africa is being courted again. This time, the language is cleaner: energy transition, critical minerals, clean infrastructure, climate finance. The urgency is sharper, the timelines are shorter, and...