Beyond the Tracks: What Africa's Mining Corridors Really Mean for the Communities They Bypass

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....

In parts of Africa, railways are being rehabilitated, ports are expanding, power lines are stretching across borders, and industrial corridors, once stalled by finance and politics, are re-entering...

"The trains pass, but we are still in the dark."

That was the quiet but piercing remark of Mariam, a farmer in northern Zambia, whose family was relocated to make way for an expanded rail line linked to the Lobito Corridor project.

She now lives further from her fields, with no electricity, no piped water, and little hope that the benefits promised will ever arrive.

As African governments and international financiers hail the Lobito Corridor as a transformative gateway for trade and critical minerals, few are asking what it means for those who live along its path.

The Lobito Corridor is being marketed as a bold leap toward regional integration and economic modernisation. Stretching from Angola to Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, it promises to accelerate exports of copper, cobalt, and other minerals essential for green technologies.

However, while the corridor is already operational within Angola, its sections in Zambia and the DRC remain largely underdeveloped and are undergoing phased rehabilitation and investment. Much of the infrastructure in these neighbouring countries requires significant upgrades before the corridor can operate as a fully functional regional trade route.

This phased state of development makes the current narrative of regional prosperity feel premature for many communities along the line.

In village after village, residents describe how the corridor has divided farmland, forced relocations, and shifted attention away from local needs.

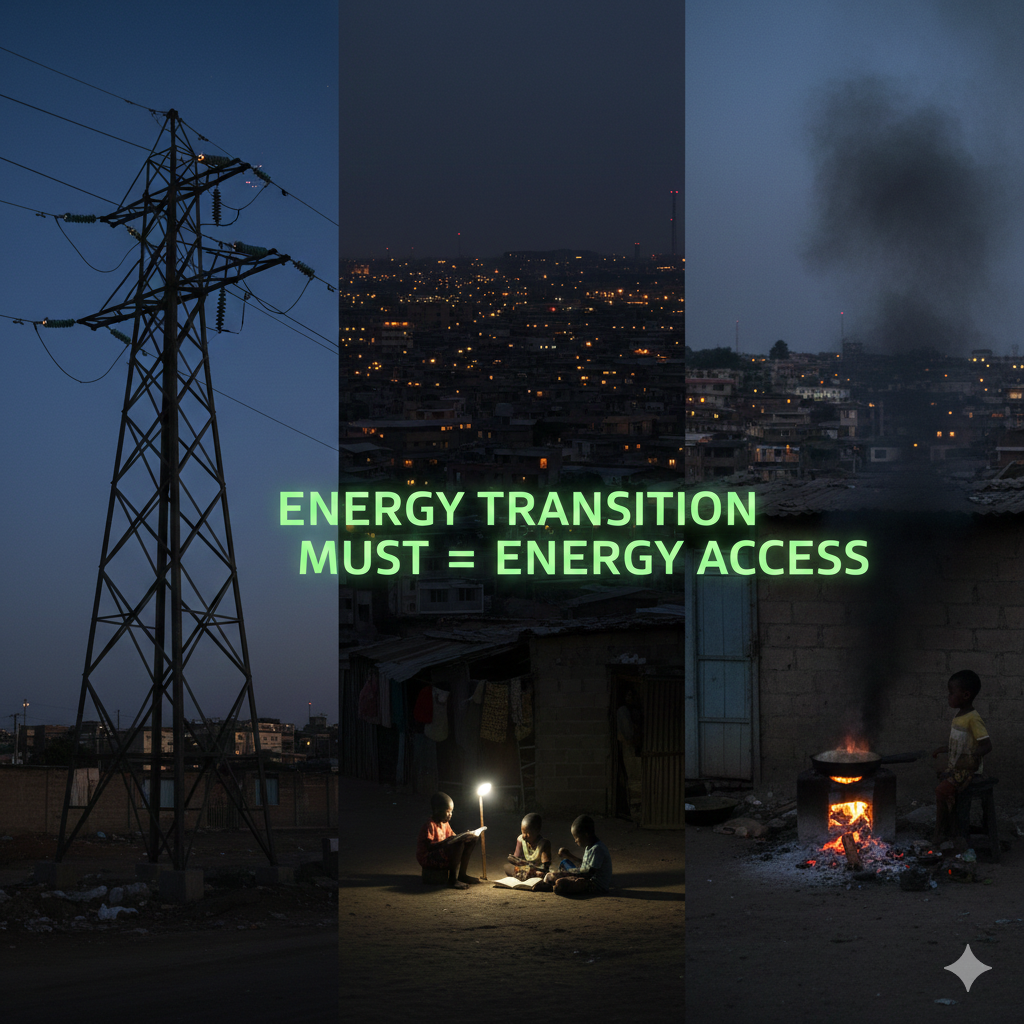

"We hear about billions being spent," says John, a community organiser from the Copperbelt. "But we still cook with firewood while the minerals under our feet light up homes in Europe."

While trains haul minerals destined for global supply chains within Angola, many towns along the broader corridor, particularly in Zambia and the DRC, remain without reliable electricity, schools, or clinics.

In some places, the railway is fenced off, restricting community movement. Compensation, when offered, is often insufficient or delayed.

Women’s groups report losing access to communal lands essential for farming and gathering firewood.

"No one consulted us," says Fatou, a market vendor in the DRC. "The project came with machines and maps, but no one knocked on our doors."

This story isn’t new. Africa's history is littered with railways built to extract resources, leaving communities impoverished while wealth flows elsewhere.

Today, the rhetoric has shifted. Instead of colonial powers, it’s multinational corporations and climate-conscious investors talking about "green corridors" and "sustainable logistics."

But the outcomes look strikingly familiar.

In our previous article, "Workers on the Frontlines: Redefining Just Transition in Africa's Green Mineral Boom", we documented how miners themselves are sidelined from decision-making in the transition narrative.

Now, it's clear that communities along infrastructure corridors face similar exclusion.

At the heart of the issue is the absence of meaningful participation.

Communities are often consulted only after major project decisions have been made, if they are consulted at all.

The principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), meant to protect Indigenous and local communities, is too often bypassed.

What residents want isn’t complicated:

"We don’t want handouts," says Mariam. "We want to be part of the future you are building through our land."

Infrastructure isn’t inherently bad. Done right, it can unlock mobility, improve trade, and connect rural communities to markets.

But it requires a different approach:

In the race to build corridors and export minerals, Africa must ask:

Are we laying tracks for prosperity or paving new paths for extraction?

Because if we cannot answer that honestly, we risk repeating the very history we say we are trying to escape.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

Africa is being courted again. This time, the language is cleaner: energy transition, critical minerals, clean infrastructure, climate finance. The urgency is sharper, the timelines are shorter, and...