The Strength of African Communities Living Without Power

For much of Africa, the diesel generator has become an unspoken pillar of the economy. It powers factories when the grid fails, keeps hospitals running during blackouts, and underwrites commercial...

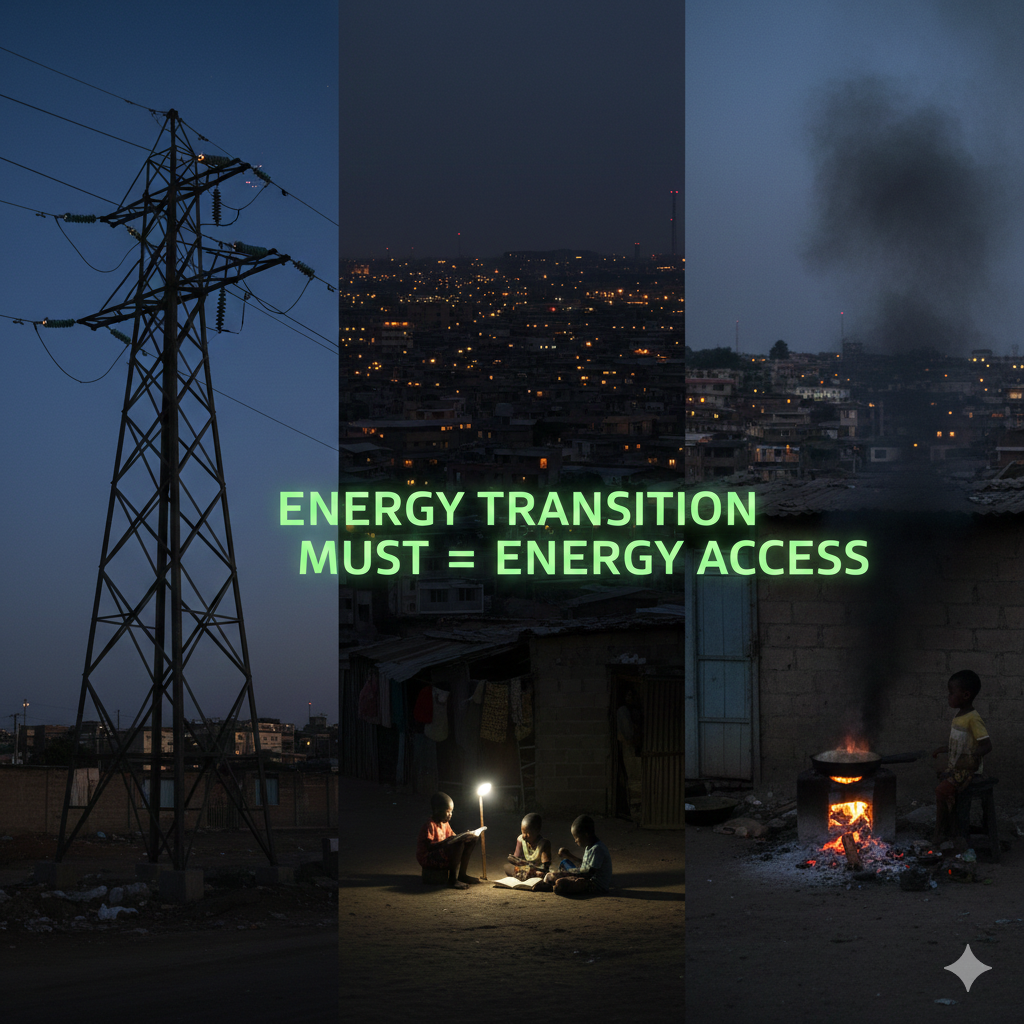

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....

There is a sound I remember from my childhood, not the noise of generators or the crackle of candles, but the soft murmur of neighbours talking in the dark. Entire evenings lit only by moonlight or the faint yellow glow of kerosene lamps. The darkness was not just an absence, it was a world, a way of living and a quiet strength.

And even now, decades later, when I visit communities across the continent, I see that same strength in places that are still waiting for light. The resilience of people who have learned to negotiate with shadows, to stretch possibility into the night, and to create meaning in places where electricity has yet to arrive.

But strength should not be mistaken for acceptance.

Resilience is not a substitute for justice.

And communities living without power are not symbols of endurance; they are victims of an energy system that has failed them.

Today, 600 million Africans still live without electricity, according to the International Energy Agency.

Behind that number are stories the world rarely hears, stories of struggle, ingenuity, loss, and dignity. Stories that remind us that energy poverty is not simply a statistical problem, but a human condition.

When policymakers speak of “off-grid communities,” the conversation quickly turns to costs, grid extension, financing frameworks and megawatt targets. But go into the villages themselves, and you will learn that electricity is not about machines. It is about people.

It is about:

Energy poverty shapes identity, possibility and destiny.

And yet, communities do more than survive.

They build, they adapt, they create new ways of life.

But should we be roamnitcising survival when we should be interrogating instead?

In a village in northern Nigeria, I once met a woman who was grinding beans using a grinding stone because she had never known stable electricity. She smiled as she worked, her arms moving in steady circles. When I asked whether she wished for a machine, she laughed softly and said:

“Of course. But until light comes, I will use what I have.” Her words were’nt a resignation but a quiet demand.

In Kenya, I met children who played in fields long after sunset because their eyes had grown used to the outlines of a world without light.

In Sierra Leone, I saw midwives who could deliver babies by torchlight, their hands steady and sure, their strength unspoken.

Across the continent, people have learned to weave meaning into the cracks left by energy poverty. But that does not make the cracks acceptable. It simply makes the people extraordinary.

Energy poverty is not neutral.

It is violent.

According to the World Health Organization, 2.3 million people die each year from household air pollution, primarily from cooking with charcoal, firewood and kerosene.

In communities living without electricity:

Darkness is not merely inconvenient. It is corrosive, and it eats away at opportunity, dignity and time.

And this is why I have repeatedly argued that energy is not a development input, but a human right. And communities have carried the cost for too long.

There is a familiar phrase in global development reports: “last-mile communities.”

It sounds logistical, but in practice, it becomes an excuse, a polite way of saying: “We don’t know how to reach them, so we won’t reach them yet.”

But these communities are not “last miles.”

They are first lives.

Many of Africa’s energy-poor communities are decades behind national averages not because they are remote, but because policy frameworks were never designed with them in mind.

A strategy that prioritises grid expansion alone will never reach them.

A financing model that rewards large-scale projects will never target them.

A governance approach that ignores local voices will never understand them.

Decentralised systems are Africa’s most realistic path to universal access.

Light must be built where people live and not where planners hope they will move.

What I admire most in communities without power isn't just their endurance, but their clarity

They know what many politicians do not say aloud:

Communities understand this intuitively because they live the consequences every day. They know that electricity is not a luxury that comes after roads and markets but It is the foundation that makes everything else possible.

And that clarity should guide us.

Africa’s energy future cannot be built only in capitals, boardrooms or climate conferences. It must be built in conversation with the people who live furthest from the light. People whose daily darkness has taught them what policymakers sometimes forget; that development begins with illumination.

To honour them, Africa must:

This is not a technical agenda. It is a moral one.

When I think of the communities living without electricity across Africa, I think of their resilience — but I refuse to romanticise it. Their strength is a testament to human will, but it should not be a requirement for survival.

Strength may carry a community through the night.

But only electricity can change what the morning looks like.

The world speaks often about Africa’s potential.

But potential, like opportunity, needs light.

And until every community across this continent has power; real power, reliable power, and dignified power, the future we imagine for Africa will remain just that: an imagination waiting for illumination.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

For years, the global energy transition has been narrated as a linear story: renewables rise, fossil fuels fall, and gas fades as a temporary bridge. That story is now colliding with reality. In late...