Oil is Still Paying the Bills: Can African Governments Afford to Let Go?

For much of Africa, the diesel generator has become an unspoken pillar of the economy. It powers factories when the grid fails, keeps hospitals running during blackouts, and underwrites commercial...

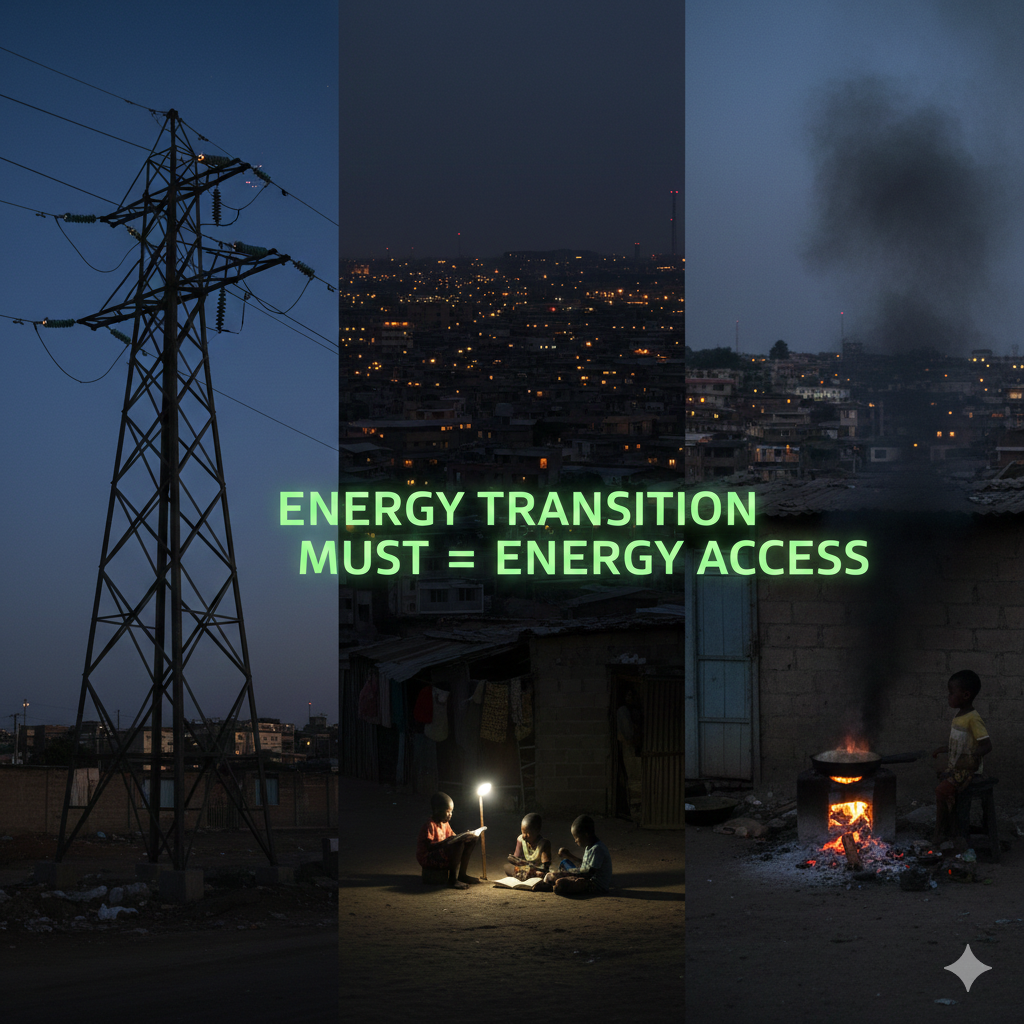

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....

It is easy to call for an end to fossil fuels from a podium in Paris. Much harder when you are in Abuja, Luanda or Brazzaville, facing empty treasuries, unpaid civil servants, and swelling youth unemployment.

As global climate campaigns grow louder, African civil society is increasingly joining the call to phase out oil, gas, and coal. However, a quiet tension lies behind the curtain: many African governments remain heavily reliant on fossil fuel revenues. For them, phasing out oil is not just about climate science; it is about fiscal survival.

For countries such as Nigeria, Angola, Algeria, Equatorial Guinea, Congo-Brazzaville, and South Sudan, hydrocarbons account for over 50% of public revenue. In Nigeria, oil and gas continue to account for nearly 80% of export earnings and over 50% of government revenue. That money pays teachers, builds roads, and keeps the lights on—however flickering they may be.

Civil society voices rightly raise alarms about stranded assets, environmental degradation, and the need for a just transition. But for treasury officials, oil remains the country’s most bankable commodity. It is the currency of their statehood.

So, how do you sunset fossil fuels when they are still the country’s sunrise money?

The fiscal pressures are brutal. Many African nations are drowning in debt. According to the International Monetary Fund, 22 African countries are either in or at high risk of debt distress. The Covid-19 pandemic pushed public spending higher, and climate disasters from floods in Mozambique to droughts in Kenya are compounding costs.

Oil, despite its volatility, remains a revenue crutch. Cutting off fossil revenues without a clear, bankable alternative risks triggering wage defaults, public unrest, and deeper borrowing.

Take Ghana. It issued green bonds, cut subsidies, and promised transition policies. But its energy sector debts now top $2.1 billion, and it recently returned to the IMF for a $3 billion bailout. It's an example that warns of how thin the financial ice is.

Fuel subsidies further complicate the picture. In Nigeria, subsidies consumed over ₦4 trillion in 2022 alone. Removing them is often seen as fiscal common sense by economists but political suicide by incumbents.

When President Bola Tinubu scrapped Nigeria’s fuel subsidy in 2023, protests erupted. Transport costs soared. Inflation spiked. Though the policy was praised by multilateral lenders like the World Bank, it eroded public trust.

For many citizens, subsidies are not just economic distortions; they are the only visible social benefit from oil wealth.

African civil society organisations are at the forefront of the climate justice movement. They are calling for a fossil fuel phaseout, for climate reparations, and for just transitions. But they also demand greater social spending, reduced debt, better healthcare, and free education.

These are legitimate demands. But they create a paradox: how can governments afford expansive social policy while unplugging their main revenue source?

Without clear pathways to replace oil revenue, civil society risks losing credibility or being painted as out of touch with fiscal realities.

In theory, green finance and Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) are supposed to fill the gap. South Africa secured an $8.5 billion JETP package in 2021. Senegal and Egypt followed. Nigeria and Kenya are next in line.

But most of these packages are a mix of loans, guarantees, and technical assistance, not direct budget support. Much of the finance is project-bound, slow-disbursing, and conditional.

Worse still, African negotiators report that donor timelines and domestic needs rarely align. You cannot fund this month’s salaries with a ten-year concessional loan for a solar park.

At the heart of the problem lies Africa’s failure to diversify. Decades of oil dependence have hollowed out industrial policy, stunted local manufacturing, and left countries vulnerable to price shocks.

Economic diversification is the way out, but it is a long, politically risky path. It requires investment, planning, and time.

Countries like Botswana (with diamonds), Rwanda (with services), and Morocco (with renewables and manufacturing) offer models. But for oil-rich giants like Angola or Nigeria, the pivot will be steep and painful.

A few imperatives are clear:

The pressure to phase out fossil fuels is not going away. Neither are Africa’s budget shortfalls. We cannot whisper about one while shouting about the other.

African governments must face a hard truth: oil wealth is a crutch, not a cure. But those calling for a phaseout must also understand that the road to net zero cannot be paved on empty stomachs or broken treasuries.

This is not about choosing between climate and development. It is about making both possible, together, deliberately, and on Africa’s terms.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

For years, the global energy transition has been narrated as a linear story: renewables rise, fossil fuels fall, and gas fades as a temporary bridge. That story is now colliding with reality. In late...