From Extraction to Industrialisation: Africa’s Critical Minerals Value Chain

For more than a decade, the global energy transition has been sold as a story of technology. We are told solar panels are getting cheaper, wind turbines are getting taller, and batteries are...

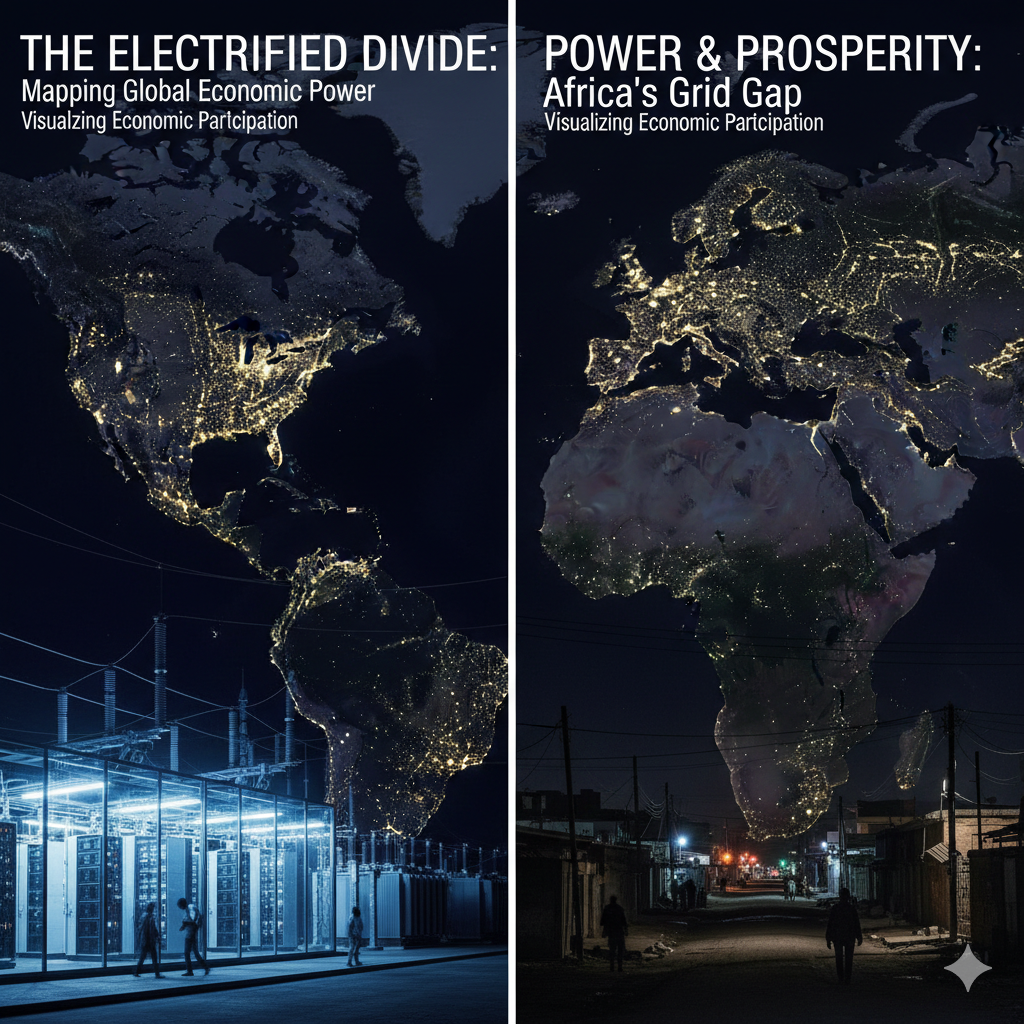

For most of modern economic history, electricity demand has followed growth. When economies expanded, electricity use rose steadily and predictably, rarely faster. That relationship is now breaking....

Africa’s critical minerals are once again in the global spotlight, but not only for what is being mined, but also for what is not being made. As the clean-energy transition accelerates, African governments and investors face a defining question: will the continent remain a supplier of raw materials, or will it build the industries that turn those minerals into value?

The answer matters. The minerals beneath African soil are essential for batteries, electric vehicles, solar panels, wind turbines, and the digital devices that power modern society. Demand for lithium, cobalt, rare earth elements, nickel, graphite, copper, and manganese is projected to surge for decades. Many of these minerals are abundant in Africa. Yet the continent captures only a small proportion of the final value created along the supply chain.

This contradiction is not new. It reflects the legacy of an extractive model that exports opportunity and imports dependency. The risk today is that a green transition built on critical minerals could still leave Africa trapped in old economic patterns.

Africa holds roughly 30 percent of global reserves of the minerals most vital to the clean-energy future. The Democratic Republic of Congo produces more than two-thirds of the world’s cobalt. Southern Africa dominates manganese. New lithium discoveries in Zimbabwe, Namibia and Malawi are drawing global attention. Mozambique and Tanzania are poised to become major graphite players.

But while Africa exports minerals, it imports most of the technologies those minerals enable. The continent plays a commanding role in the first step of global value chains, and a negligible role in every step thereafter.

It is a familiar tale:

Industrialisation ambitions have been expressed in policy after policy. Implementation has not kept pace.

The gap between extraction and industrialisation is driven by a combination of structural barriers.

Investors continue to see African downstream projects as risky. Foreign-currency loans expose countries to exchange-rate shocks. Domestic banking systems have limited capital for long-term industrial investment.

Mining attracts investment. Processing does not, yet.

Battery-grade chemical refining, rare-earth magnet production and cathode manufacturing require advanced capabilities that few African countries currently possess. The result is technological dependency at the precise point where the most value is created.

Downstream processing requires abundant electricity, water, transport corridors and efficient logistics. Many mineral belts remain far from the infrastructure needed for globally competitive manufacturing.

Export bans, beneficiation mandates and incentives are often introduced abruptly or without regional alignment. The result is regulatory uncertainty rather than investor confidence.

Major economies are treating critical minerals as strategic assets. Without coordinated bargaining power, African governments negotiate separately, weakening collective leverage.

These forces combine to keep Africa at the extractive end of the chain, even as global demand expands.

Despite headwinds, the pathway to industrialisation is beginning to open. Several shifts are working in Africa’s favour.

For the first time in decades, Africa has both mineral leverage and geopolitical attention. The question is whether it can convert interest into industry.

Moving from extraction to industrialisation demands strategic clarity. Industrial policy must define where Africa wants to compete, and how.

The most promising areas for value capture include:

In each of these steps, the value created is many multiples higher than in raw-ore export.

Industrialisation is not simply an economic upgrade. It shifts power, ownership and governance. It changes who decides how Africa’s minerals are used, and who benefits when they are.

Africa’s industrial transition requires a structural break from the past extractive model.

1. An Africa-wide strategy

Africa needs unified negotiating positions for global critical-minerals markets, not 50 separate voices. Regional value chains cannot succeed without policy coordination.

2. Capital that stays and circulates on the continent

Local-currency finance from African banks, pension funds and development institutions must scale dramatically. If capital comes only from outside, so will control.

3. Skills and technology transfer anchored at home

Industrialisation must build African expertise, not simply lease foreign equipment and consultants.

4. Infrastructure designed around industry

Transport corridors, special economic zones and reliable power must align with mineral-processing hubs.

5. Social inclusion and environmental protection

Local communities must share in revenues and jobs. Environmental safeguards must be strong, enforced and domestically owned.

This is how critical minerals become catalysts for transformation rather than symbols of inequality.

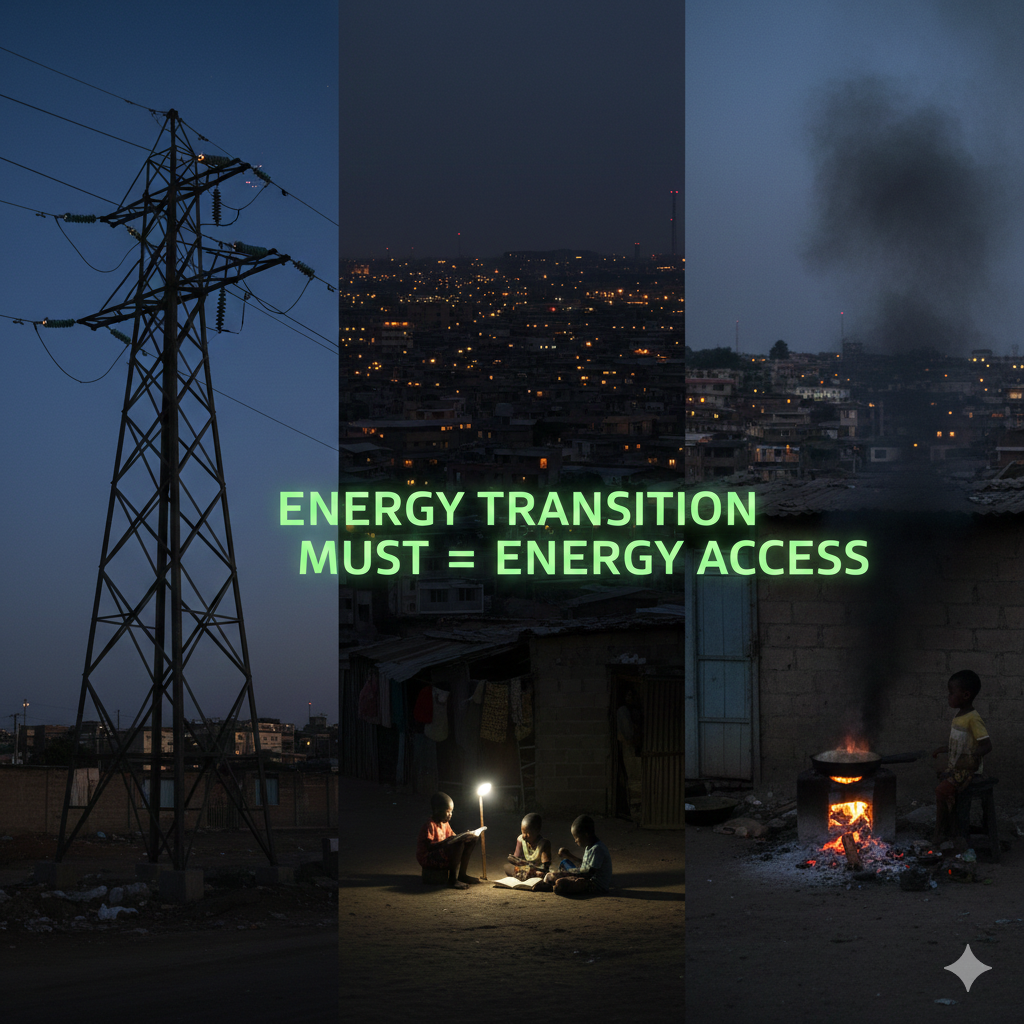

Much of the global debate on a “just energy transition” focuses on coal phase-out and renewable deployment. For Africa, justice must also apply to the minerals powering that transition.

A just minerals future requires:

• Fair value capture in African economies

• Transparent contracts and clean governance

• Workers’ rights and community participation

• Environmental stewardship from mine to factory

• Industrial growth that supports energy access and development

Justice is not a slogan. It is a structure.

Critical minerals represent a once-in-a-century industrial opening. If Africa fails to industrialise now, it may miss the economic wave shaping the rest of the 21st century. If it seizes the moment, it could emerge as a global player, not merely the marketplace for finished goods, but a manufacturer of the technologies that power the future.

Africa has been here before: vital to global industry, yet peripheral to its value. This time, the stakes are higher. The green transition cannot be clean if it repeats the injustices of the fossil-fuel economy.

Industrial sovereignty, not extraction, must be the foundation of Africa’s minerals future.

The world needs Africa’s resources. Africa must ensure it needs Africa’s industry too.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....