Africa’s Energy Transition Standstill: Why Sub-Saharan Readiness Is Failing to Improve

For much of Africa, the diesel generator has become an unspoken pillar of the economy. It powers factories when the grid fails, keeps hospitals running during blackouts, and underwrites commercial...

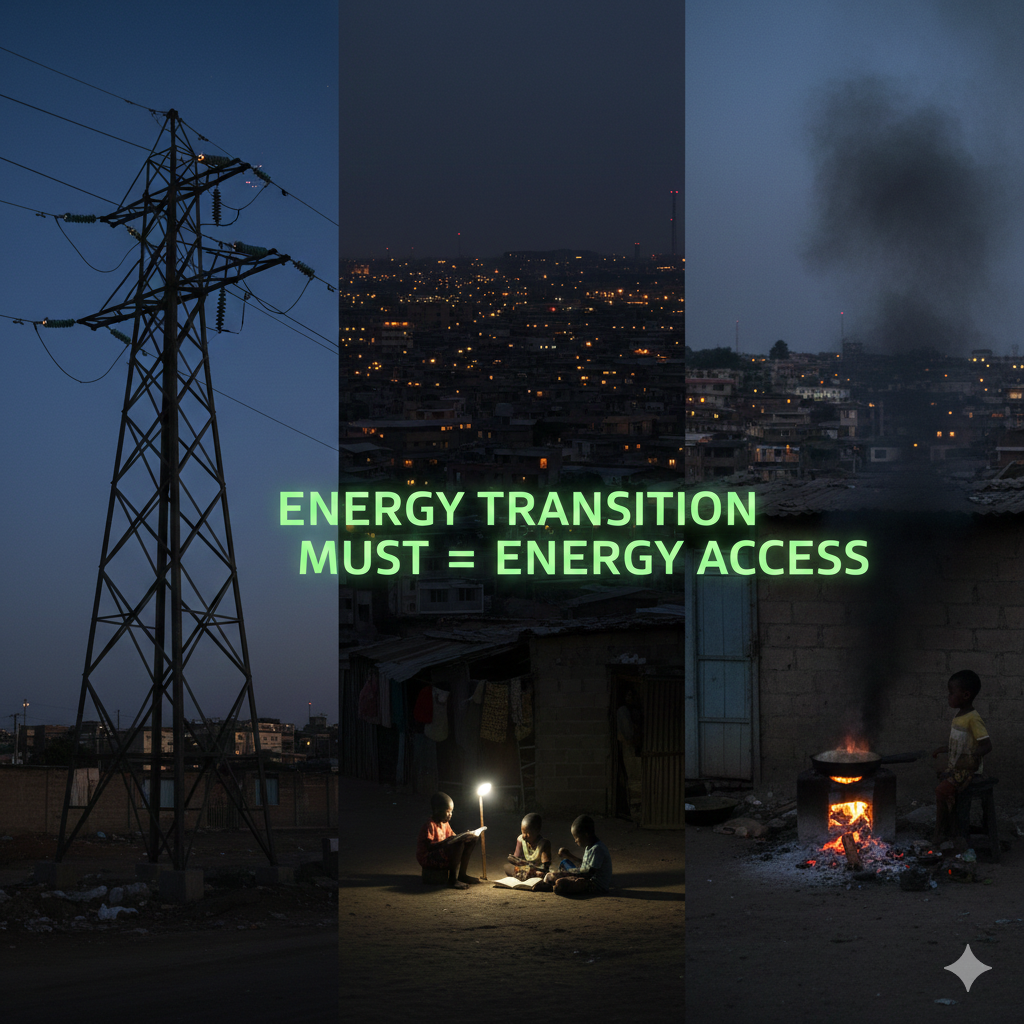

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....

Even as the narrative of Africa’s renewable potential grows louder, the latest data reveals a sobering reality. Sub-Saharan Africa’s ability to transition from fossil fuels to clean power has stalled. According to the World Economic Forum’s latest Fostering Effective Energy Transition assessment, the region registered no year-on-year improvement in energy transition readiness for 2025. The score remains flat, despite a decade of declarations and high-profile climate pledges.

This stagnation raises a critical question. How can the region simultaneously rank among the world’s richest in renewable resources and yet be the least ready to transition? The gap between promise and progress is widening, not closing. If Africa is to participate meaningfully in the global shift to cleaner energy, the region must confront the financing, governance, and political obstacles preventing transitions from moving beyond ambition.

Sub-Saharan Africa possesses vast renewable endowments. The African continent holds more than 60 percent of the world’s best solar resources. SEforALL estimates that renewable energy capacity in Sub-Saharan Africa could triple by 2030, unlocking a market worth USD 27 billion in new industries and green manufacturing.

Yet the region remains the least electrified in the world. More than 600 million people still lack access to electricity, and those who are connected face some of the highest power costs relative to their income globally. Without major changes to how power systems are financed and governed, the region’s energy future will continue to lag behind its potential.

Three years ago, development institutions projected that Africa could leapfrog fossil fuels. Today, that confidence has cooled. Project after project faces delays, stalled financing decisions, and persistent governance hurdles.

A renewable-powered future will not materialise through resource abundance alone.

The cost of capital remains the single biggest barrier to clean-energy development in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Local developers often pay 12 to 20 percent interest to borrow for renewable projects up to four times the financing cost in Europe or China. The reason is less about project risk and more about perceived risk. Currency fluctuations, sovereign-credit ratings, and thin capital markets inflate premiums far above actual market conditions.

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle. High finance costs make projects expensive; expensive power slows electrification; slower electrification erodes investor confidence, resulting in even higher risk pricing.

Most renewable projects rely heavily on external financing denominated in dollars. When local currencies weaken, repayment obligations surge, threatening utility solvency and public finances. It is a vulnerability built into the financing model itself.

Unless capital becomes affordable on African terms, energy transitions will remain aspirational.

While clean-energy targets multiply, fossil-fuel systems continue to dominate in practice.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s grid infrastructure still revolves primarily around thermal power. Nigeria’s economy is structurally dependent on oil; South Africa’s employment landscape is still anchored to coal; countries such as Mozambique and Senegal rely on new gas developments to secure export revenue and foreign investment.

When national budgets depend on fossil fuels, the pace of transition slows. Governments that fear fiscal instability are less likely to set firm fossil-fuel phase-out timelines, reform subsidies, or secure concessional finance.

The result: new fossil investments being locked in just as the world demands their retirement.

The transition is being slowed not just by technology or cost, but by institutional capacity.

Key shortcomings include:

These are not technical issues; they are political economy barriers. Even where strong policies exist, implementation lags because of competing interests, short-term political horizons, and fragmented coordination between ministries, utilities, and regional bodies.

Without accountable, data-driven governance, even the best policy declarations fade quickly into paper commitments.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s transition is inseparable from social justice. Any delay in progress has cascading consequences:

The ILO estimates that up to 25 million African jobs could be created through green-sector investments by 2030, yet that opportunity remains theoretical unless access expands rapidly.

The longer transitions stall, the deeper inequality becomes.

Despite current stagnation, new strategic openings are emerging.

Power pools in West, East, Central, and Southern Africa can reduce overall system costs through:

Regional planning lowers investment risk for large-scale renewables and storage.

The UN’s industrial hub model suggests Africa can build:

Capturing just 10 percent of projected global green-tech investment could add USD 56 billion annually in value.

New financing tools (including Article 6 mechanisms and green infrastructure bonds) create chances to monetise emissions reductions and invest proceeds locally.

Carbon trading must be designed to ensure:

African lenders and pension funds are increasingly willing to participate in grid upgrades, mini-grids, and residential solar. Local-currency lending reduces exposure to exchange-rate shocks and aligns financing with domestic economies.

These opportunities demand one precondition: credible policy signals.

To shift from stagnation to acceleration, the region must pursue five priorities:

These steps form a practical blueprint for readiness, the missing ingredient in Sub-Saharan Africa’s transition journey.

Global climate diplomacy has offered African governments a long runway for ambition. That era is ending. Investors and international partners no longer reward declarations without delivery.

The longer readiness remains flat, the more the region risks:

Sub-Saharan Africa’s transition gap reflects not a failure of potential, but a failure of preparation.

The clock toward 2030 is not slowing. The transition must accelerate, now, not later.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

For years, the global energy transition has been narrated as a linear story: renewables rise, fossil fuels fall, and gas fades as a temporary bridge. That story is now colliding with reality. In late...