COP30 Launched a Just Transition Mechanism, But Will It Change Anything for African Workers?

For more than a decade, the global energy transition has been sold as a story of technology. We are told solar panels are getting cheaper, wind turbines are getting taller, and batteries are...

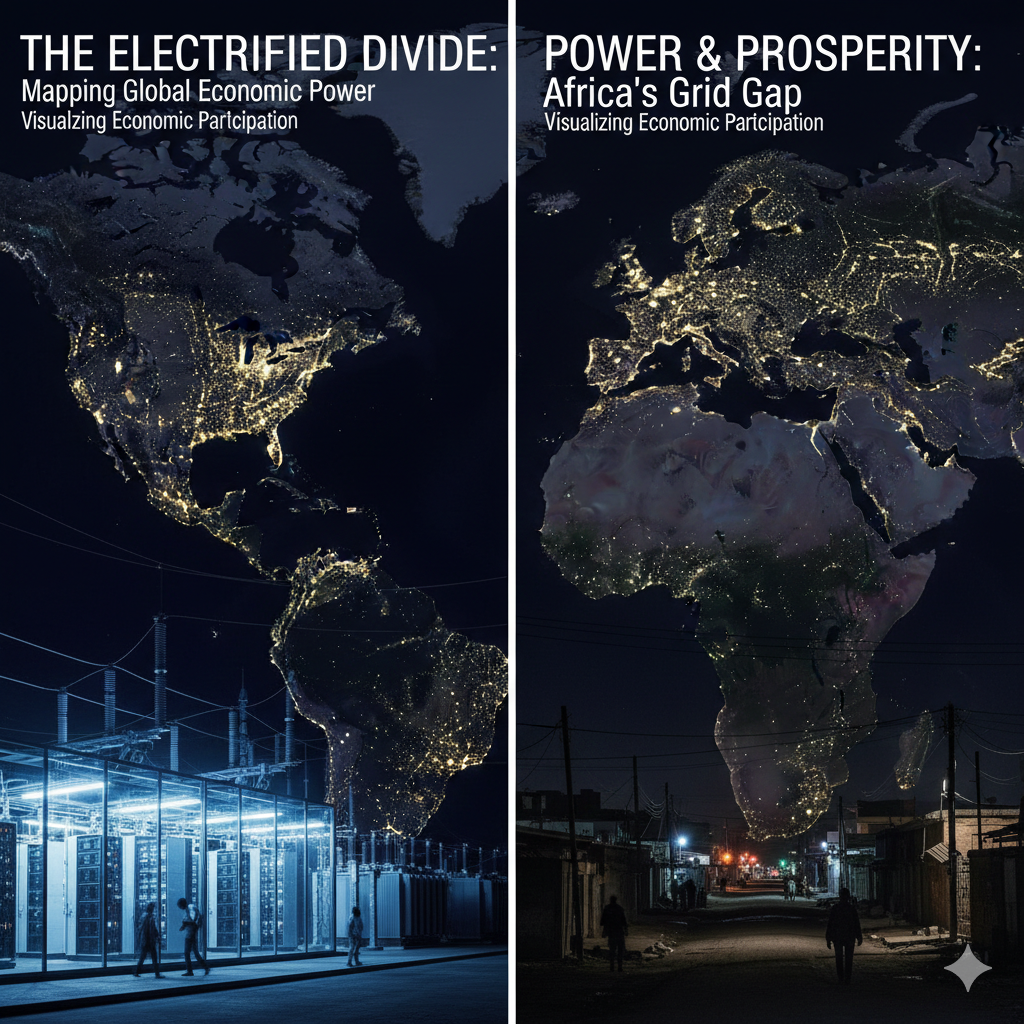

For most of modern economic history, electricity demand has followed growth. When economies expanded, electricity use rose steadily and predictably, rarely faster. That relationship is now breaking....

COP30 introduced a new global Just Transition Mechanism, a framework meant to protect workers and communities as the world accelerates away from fossil fuels.

It sounded momentous, the kind of policy breakthrough climate summits are expected to deliver. A global commitment to fairness. A promise that no worker, in no community, would be left behind.

But outside the air-conditioned halls, in the coalfields of Mpumalanga, the gas belt of Mozambique, or the oil terminals of the Gulf of Guinea, that announcement had little impact. The mechanism comes without funding. No guarantee of reskilling. No safety net. No labour insurance. No community transition fund.

A mechanism without money is not a plan.

It is a suggestion, and a fragile one.

For African workers, who stand at the frontlines of the global energy transition, the question now is painfully simple:

Will the COP30 Just Transition Mechanism actually change anything?

The Just Transition Mechanism is being framed as the world’s answer to growing labour anxiety. It is described as a global coordination hub, a set of guiding principles, and a new reporting platform for countries to detail their plans for workers as fossil fuels decline.

But look closely at what it offers and what it does not, and the gap becomes clear.

What it offers:

What it does not offer:

This is the paradox:

The world has acknowledged the human cost of the transition, but has not decided to pay for it.

In Africa, where labour markets are already fragile and fossil jobs often support entire communities, this omission casts a long shadow.

The energy transition may be global, but its labour impact is deeply uneven.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that millions of African workers are employed directly or indirectly in fossil-fuel industries, from coal mining to oil refining to gas logistics.

But the decline is already underway:

Meanwhile, the green economy is not yet delivering jobs at scale.

The IEA expects clean-energy technologies to create 30 million new jobs by 2030, yet only a sliver will be in Africa without targeted investment.

The IRENA 2024 jobs report shows 16.2 million renewable workers globally, but Africa remains largely absent.

The result?

Africa is being pushed out of one global labour market before it is invited into the next.

COP30’s mechanism recognises this imbalance with diplomatic language. But recognition is not protection.

The world imagines the transition in timelines: 2030, 2050, 2060.

Workers in Africa experience it in bills paid or not paid; contracts renewed or not renewed; shifts assigned or quietly cancelled. The transition is not theoretical. It is Thursday afternoon when a supervisor tells a team the plant will close early next year, and the company has no retraining plan.

For a coal truck driver in Emalahleni, a refinery technician in Port Harcourt, or a pipefitter in Pemba, a “just transition” must be more than a slogan. It is the difference between descent and dignity.

What COP30 did, to its credit, is make labour impossible to ignore.

What it failed to do is make protection inevitable.

A mechanism without funding is not entirely powerless. It can still be a lever.

African unions can now push governments and companies to:

“COP30 requires this” is a powerful bargaining tool.

Most African governments have no public roadmaps for fossil-dependent regions. The mechanism requires reporting. Reporting creates accountability.

Companies operating in Africa can no longer ignore transition obligations they follow in Europe or Australia.

Communities in mining and oil regions can demand CBAs —community benefit agreements, tied directly to COP30 principles.

Equity cannot be afterthought.

The real question is not whether COP30 delivered enough. It didn’t.

The question is whether African states seize the moment to lead.

Here’s what must happen immediately:

South Africa has one.

Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, Mozambique must follow.

These commissions must map:

No new solar park, hydrogen hub, or gas field should proceed without a skills and worker-transition budget.

This is the heart of Energy Transition Africa’s ongoing work on the continent’s skills as infrastructure crisis.

Developed economies cannot preach justice while underfunding it.

Transition without jobs is instability.

Instability is expensive.

Investment is cheaper than unrest.

Utility transitions, from Eskom to Tanesco, will create more labour turbulence than coal mines. Planning must begin now.

The mechanism gives legitimacy to labour demands.

Communities must not wait to be “consulted”.

They must shape the process.

The mechanism requires reporting.

Workers must track, and contest, what gets filed.

A transition without funding is not a transition, it is abandonment.

The COP30 Just Transition Mechanism is not the solution African workers hoped for.

But it is a beginning, fragile, incomplete, symbolic, yet still a beginning.

What happens next will be determined not by the text of a UN decision, but by what unions demand, what governments prioritise, what industries negotiate, and what communities insist upon.

A global transition built on the back of unprotected labour is neither just nor durable.

Africa’s workers do not fear the transition.

They fear being ignored by it.

And now that the world has acknowledged their place in the story, they must not be written out of its next chapter.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

As Mining Indaba opens in a few days, one point of alignment is already clear: value addition has become the dominant political language around Africa’s future in critical minerals. From policy...