What Happens to Climate Negotiations When Big Emitters Walk Away

For more than a decade, the global energy transition has been sold as a story of technology. We are told solar panels are getting cheaper, wind turbines are getting taller, and batteries are...

For most of modern economic history, electricity demand has followed growth. When economies expanded, electricity use rose steadily and predictably, rarely faster. That relationship is now breaking....

For years, global climate negotiations have relied on a fragile yet powerful idea: that collective action, however imperfect, is preferable to unilateral drift. The machinery of climate governance was built on this premise: slow-moving, consensus-driven, and often frustrating, but anchored in the belief that shared rules create shared responsibility.

When a major emitter steps away from that system, the consequences are neither symbolic nor contained. They ripple through finance, reporting, accountability, and trust, reshaping what climate negotiations can realistically deliver.

This explainer sets out how UN climate governance actually works, what breaks when a big player exits, and why the effects are felt most sharply by countries that rely on predictability rather than power.

At the centre of global climate negotiations sits the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the legal and diplomatic framework adopted in 1992 to coordinate international action on climate change.

The UNFCCC does three core things:

In short, the UN system doesn't enforce climate action. It coordinates it. Its power lies in norms, transparency, and collective pressure.

When a large economy disengages from UN climate frameworks, three things happen almost immediately.

Climate negotiations depend on reciprocity. Countries commit, in part, because they believe others will do the same.

When a major emitter steps back, it sends a signal, intended or not, that collective restraint is optional. This weakens the incentive for ambitious commitments across the board, particularly among countries already balancing climate action against development pressures.

And this has a cumulative effect, with vaguer targets, softer language and stretched timelines.

One of the UNFCCC’s achievements has been the normalisation of emissions reporting and review. Even when compliance is imperfect, the expectation of disclosure matters.

When a major player exits, while it doesn't stop reporting, it may undermine the authority of the system itself. Other countries may still comply, but the perception of uneven scrutiny erodes trust.

Transparency without universality becomes politically fragile.

Without a strong multilateral anchor, accountability moves from agreed rules to bilateral leverage and reputational pressure.

This favours actors with market power, financial clout, or geopolitical influence. It disadvantages those whose main protection lies in shared norms.

When big emitters walk away, climate governance tilts.

One of the least understood consequences of weakened multilateralism is its impact on climate finance.

Under the UN system, finance commitments, however insufficient, are framed as part of a shared global effort. This framing matters because it:

When a major player disengages, climate finance becomes more fragmented and political.

Institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund continue to operate, but the environment around them changes. Donor coordination weakens, bilateral priorities harden, and funding shifts from pooled mechanisms to strategic deals.

For recipient countries, this makes long-term energy planning more difficult. Predictability declines, conditionality increases, and grants give way to loans and guarantees.

Climate finance becomes harder to aggregate and easier to politicise.

When major emitters disengage, COPs themselves change character.

Negotiations become less about collective trajectory and more about damage control, preserving language, defending processes, and preventing backsliding. The agenda narrows, and procedural battles intensify.

Smaller and more vulnerable countries often find themselves expending political capital simply to keep frameworks intact, rather than pushing ambition forward.

This creates a paradox: the system continues to meet, but its centre of gravity shifts from progress to preservation.

Beyond finance and targets, UN climate negotiations shape standards for carbon markets, reporting methodologies, adaptation metrics, and climate risk disclosure.

When a major emitter steps away, these standards may not vanish, but their universality is compromised.

Private actors, investors, insurers, and companies may still adopt them, particularly where markets demand it. But governments become more selective.

This fragmentation increases transaction costs and uncertainty, particularly for countries trying to integrate into global clean energy markets.

Large economies can afford fragmentation. They can negotiate bilaterally, shape standards through markets, and absorb uncertainty.

Countries without that leverage rely on rules that apply to everyone.

For them, multilateral climate governance is not an abstract ideal, but a source of protection, however imperfect, against arbitrary power.

Multilateralism matters most to those who have the least leverage without it.

It is important to be clear about what a major exit doesn't mean.

Markets, subnational actors, and other governments continue to move often faster than negotiations.

But the centre of coordination weakens, and with it the ability to align action at scale.

The greatest danger is not any single exit. It is the precedent.

If disengagement becomes normalised, climate governance risks sliding from a rules-based system into a patchwork of voluntary alignment and power-based bargaining.

Over time, this could hollow out the very mechanisms designed to ensure fairness, transparency, and accountability.

In practice, countries respond to weakened climate negotiations in three ways:

These adaptations are rational. They are also uneven, favouring countries with capacity and coordination.

Despite its flaws, the UN climate system remains the only forum where:

Even weakened, it provides reference points that other institutions and markets rely on.

Abandoning it entirely would not create a stronger system. It would create many weaker ones.

When big emitters walk away, climate negotiations don't end. They become more complex, more political, and less forgiving of vagueness.

The era of easy consensus is gone. What remains is a landscape where clarity, credibility, and coordination matter more than ever.

For countries navigating this shift, the lesson isn't despair but realism. Climate governance is entering a harder phase, one where strategy matters as much as solidarity.

The rules still exist, but the question is how many will choose to play by them and what happens when they do not.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

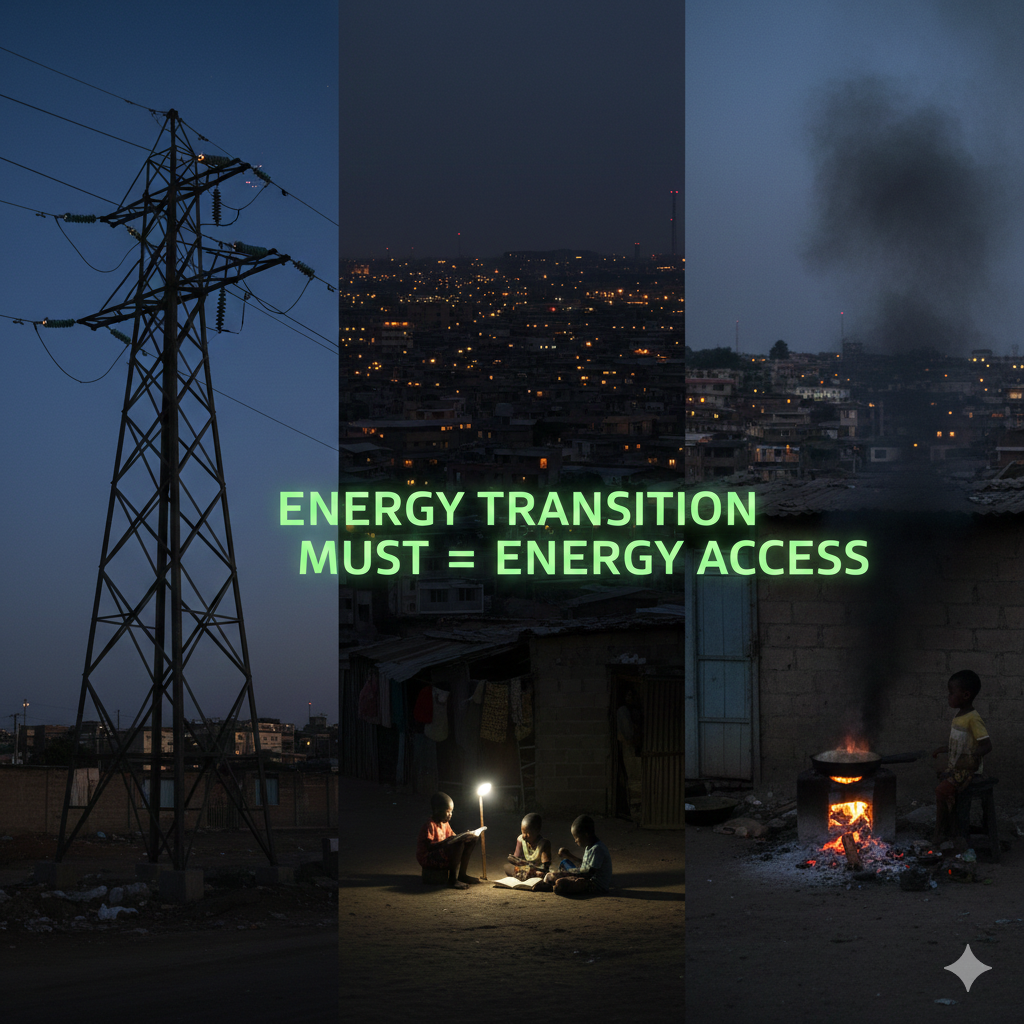

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....