Africa’s Energy Paradox: Powering the Global Transition While Living in the Dark

For more than a decade, the global energy transition has been sold as a story of technology. We are told solar panels are getting cheaper, wind turbines are getting taller, and batteries are...

For most of modern economic history, electricity demand has followed growth. When economies expanded, electricity use rose steadily and predictably, rarely faster. That relationship is now breaking....

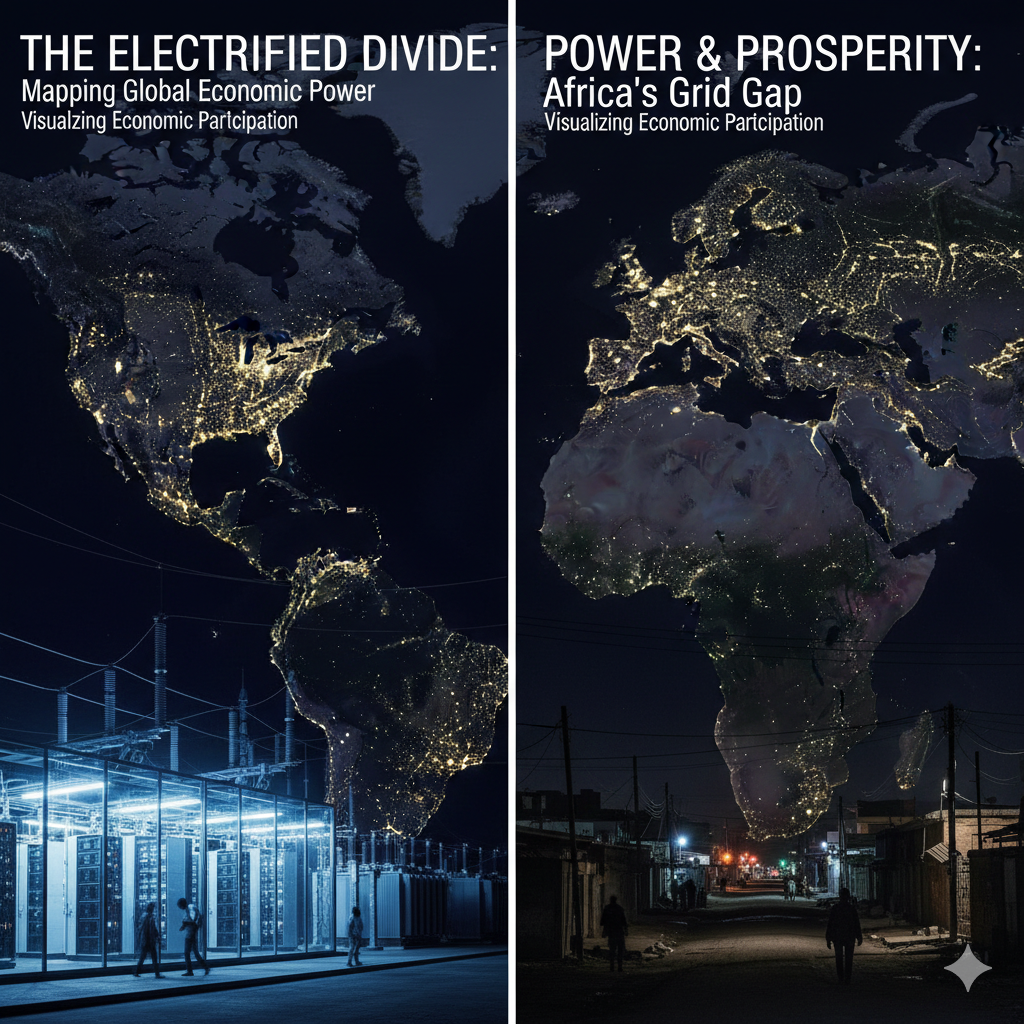

Africa is central to the global energy transition, yet marginal within it.

The minerals that make modern clean energy possible are increasingly sourced from Africa. Cobalt stabilises batteries, copper carries electricity, lithium stores power, manganese, graphite and nickel underpin the technologies that wealthy economies now treat as strategic assets.

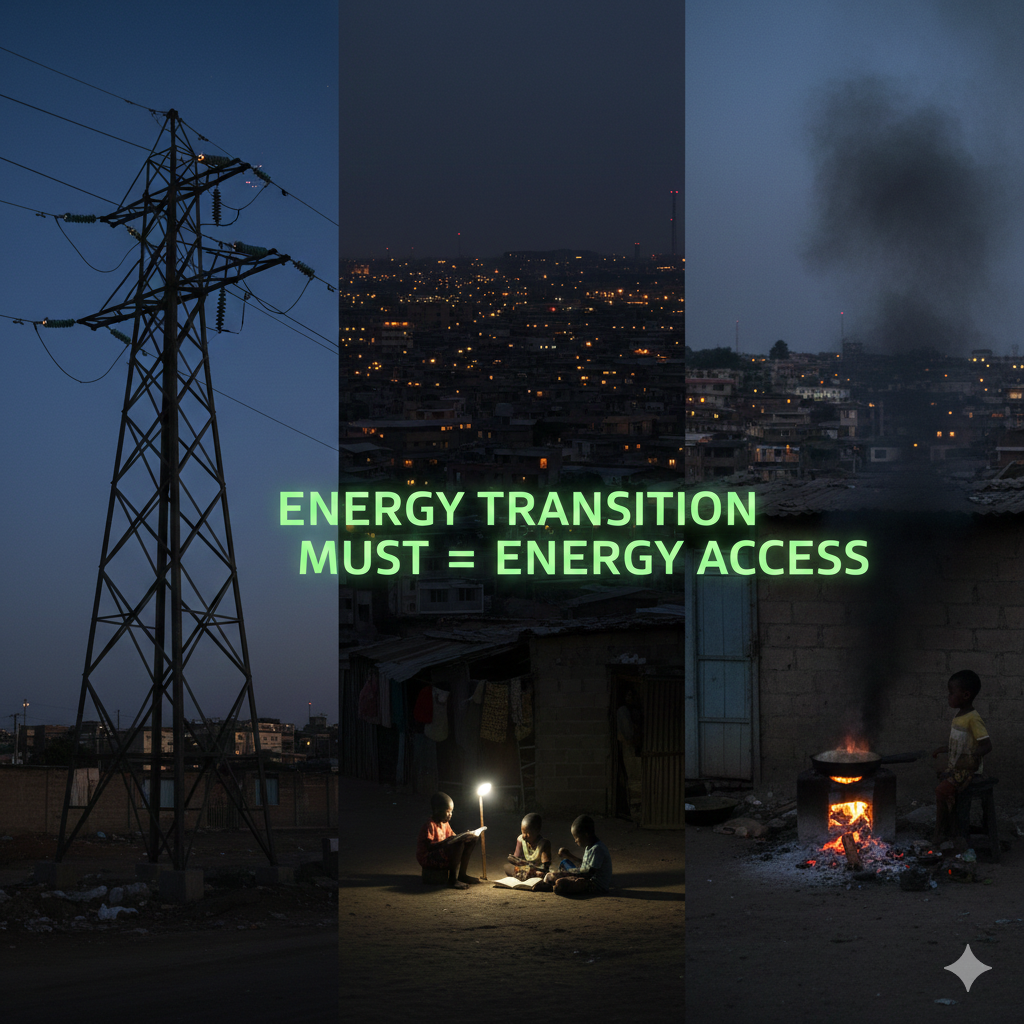

And yet, across the same continent supplying these inputs, more than 600 million people still live without reliable electricity. Hospitals ration power, small businesses run diesel generators that cost more than the profits they generate, students revise by torchlight, and factories sit idle not for lack of labour or demand, but for lack of current.

This is Africa’s energy paradox: powering the world’s transition while living in the dark.

It is often framed as a tragedy. Sometimes as inevitability, and too often as a problem of time. Yet it is none of these, but a result of bad choices.

The clean energy transition is usually narrated through images of solar farms, wind turbines and electric vehicles. Africa appears in that story mainly as a supplier of minerals, land, offsets, or impact metrics. Rarely as a beneficiary.

According to the International Energy Agency, demand for critical minerals could quadruple by 2030 as countries scale renewables, storage and electric mobility. Africa holds a significant share of these reserves, including dominant positions in cobalt, manganese and platinum-group metals.

This mineral endowment has made Africa strategically important to the transition, yet it hasn't made Africa reliably electrified. The paradox is stark: the continent enabling clean power elsewhere remains energy-poor at home.

Energy poverty in Africa is often explained away with familiar arguments: scale, poverty, weak institutions, and difficult terrain. But these explanations collapse under scrutiny.

Africa isn't short of energy resources. It has some of the world’s best solar and wind potential, vast hydro resources, geothermal capacity, and, controversially but undeniably, natural gas. It isn't short of demand, nor is it short of global capital interest.

What Africa lacks isn't energy, but delivery systems.

Electricity systems are built or broken by planning, regulation, tariffs, maintenance, and institutional discipline. The distance between mineral wealth and power access isn't geological, but political.

Africa’s energy poverty is not a resource problem. It is a systems problem.

One of the clearest expressions of the paradox is this: minerals move more reliably than electricity.

Across the continent, extractive projects often enjoy:

Meanwhile, the towns and regions around them experience outages, voltage instability, or no service at all.

This dual system, reliable power for extraction, unreliable power for citizens, reflects priorities embedded in contracts, planning decisions, and political incentives.

Railways are built to ports before grids are reinforced to communities. Mines are connected to export corridors before industrial parks are connected to substations. The transition, in this form, is something Africa supplies, not something it lives.

Energy poverty, besides being an inconvenience, is also an economic and moral tax paid daily.

The World Bank has repeatedly shown that unreliable electricity reduces productivity, raises business costs, discourages manufacturing, and entrenches informality. Firms invest in generators instead of growth. Hospitals divert funds from care to fuel, and schools lose learning hours.

These costs rarely appear in global discussions about critical minerals or clean energy supply chains. The urgency is always upstream about securing inputs and stabilising prices. Downstream, in African households and enterprises, the transition remains abstract.

Africa pays twice for the energy transition: once by exporting its minerals, and again by importing darkness.

A common defence of the current model is sequencing: export first, electrify later. Mineral revenues will eventually fund infrastructure. Time will close the gap.

History offers little support for this optimism. Resource revenues do not automatically translate into public goods, especially in power sectors plagued by tariff politics, weak utilities, and fragmented planning. Electricity systems require deliberate, upfront investment, not residual funding.

Waiting for minerals to “pay for” electrification isn't a strategy. It is a postponement. This is why the paradox persists decade after decade: extraction is treated as urgent; electrification as eventual.

The global energy transition is often described as universally beneficial. In practice, its early gains are unevenly distributed.

Industrialised economies capture:

Resource-rich regions capture extraction rents, often volatile and limited.

Without intentional policy, Africa risks becoming the fuel station of a green world: essential, profitable for others, and structurally peripheral.

This isn't because the transition is malicious, but because markets follow incentives, and incentives haven'tt been aligned with African electrification.

Solving Africa’s energy paradox doesn't require new technology or global charity; it requires policy alignment. And four shifts matter most.

Power for households and businesses must be treated with the same urgency as power for mines and export corridors.

Mining licences and corridor agreements should embed obligations for grid investment, system reinforcement, or community power delivery, not as philanthropy, but as economic logic.

Installed capacity is meaningless without reliability. Distribution, maintenance, and grid management are where transformation happens.

Africa’s minerals, manufacturing ambitions, and power systems must be planned together, or none will work well.

An energy transition that leaves its suppliers in the dark is not a transition. It is extraction with better branding.

Every element of this paradox reflects a decision:

None of these choices is inevitable.

Africa’s persistent energy poverty is not evidence of incapacity. Electrification has too often been treated as a social objective rather than a core economic priority. And the result is a continent indispensable to the future, yet underserved in the present.

There is a moral dimension to this story, but it isn't about guilt, but about coherence.

If Africa is good enough to supply the minerals that power clean futures elsewhere, it is good enough to demand reliable power at home. If the transition is truly about justice, it cannot accept a system where extraction accelerates while electrification stalls. This is the logic that makes the continent's strongest argument.

As climate finance fragments and critical minerals become geopolitical assets, Africa’s leverage is growing, but so is the risk of repeating old patterns under new names.

This paradox is the anchor for every serious transition debate:

It is the story that connects justice to systems, and morality to infrastructure.

Africa’s energy paradox is not that it lacks power. It is that its power points outward.

Until policy realigns extraction with electrification, the continent will continue exporting the future while living without it.

That isn't a tragedy of geography, but a failure of choice.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....