Africa’s Solar Skills Crisis: Why the Continent’s Clean Energy Future Depends on the People We’re Leaving Behind

For more than a decade, the global energy transition has been sold as a story of technology. We are told solar panels are getting cheaper, wind turbines are getting taller, and batteries are...

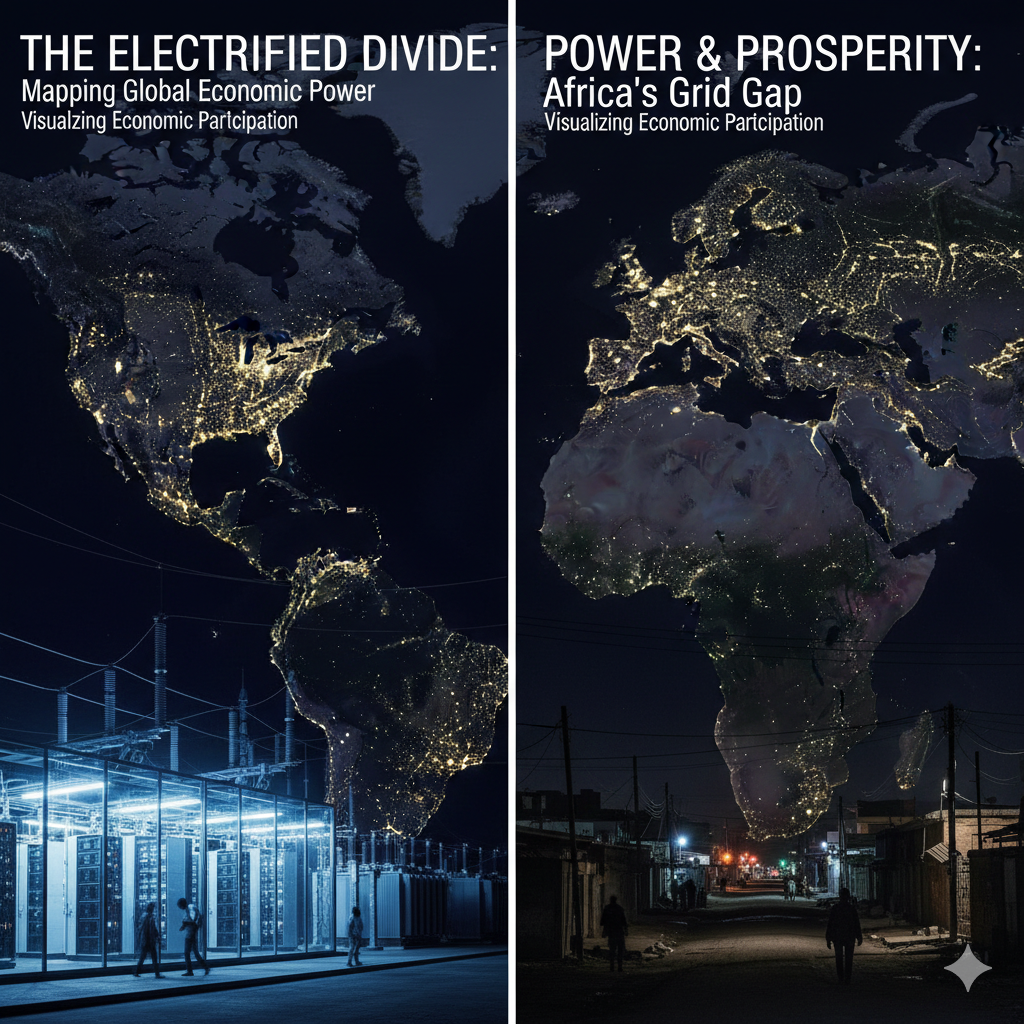

For most of modern economic history, electricity demand has followed growth. When economies expanded, electricity use rose steadily and predictably, rarely faster. That relationship is now breaking....

Not long ago, I stood near a primary school building in northern Nigeria. A technician was fastening a solar panel to the roof of one of the school buildings. The schoolyard buzzed with the laughter and dust of children at break time, their joy rising over the quiet hum of the countryside. Their teachers told me that when the system finally came online, it would be the first time in years the school had reliable power.

As I watched him work, a question settled into my mind with an uncomfortable weight:

What happens when we run out of young people like him?

What happens when Africa’s solar ambitions outgrow Africa’s solar workforce? Standing there and watching the young man work, I realised something we don’t say loudly enough:

Africa has no shortage of sunlight. What we lack dangerously are the skilled hands to turn that sunlight into power.

Across the continent, renewable energy is experiencing the kind of acceleration many of us dreamed about a decade ago:

In numbers, the story reads like progress, but in reality, it is far more fragile.

Because while solar panels can be imported, installed, financed or subsidised, there is no substitute for a trained workforce. And right now, Africa is experiencing a silent shortage, a skills drought that threatens to stall the clean energy moment we’ve waited generations to see.

The IEA estimates that Africa will need more than 2 million new clean-energy workers by 2030, with solar representing the bulk of that demand. Today, we have only a small fraction of those workers, dispersed unevenly across the continent.This is not a future crisis. Rather, it is a present one.

The global clean energy sector has its own skills challenges. But in Africa, the consequences are uniquely sharp.

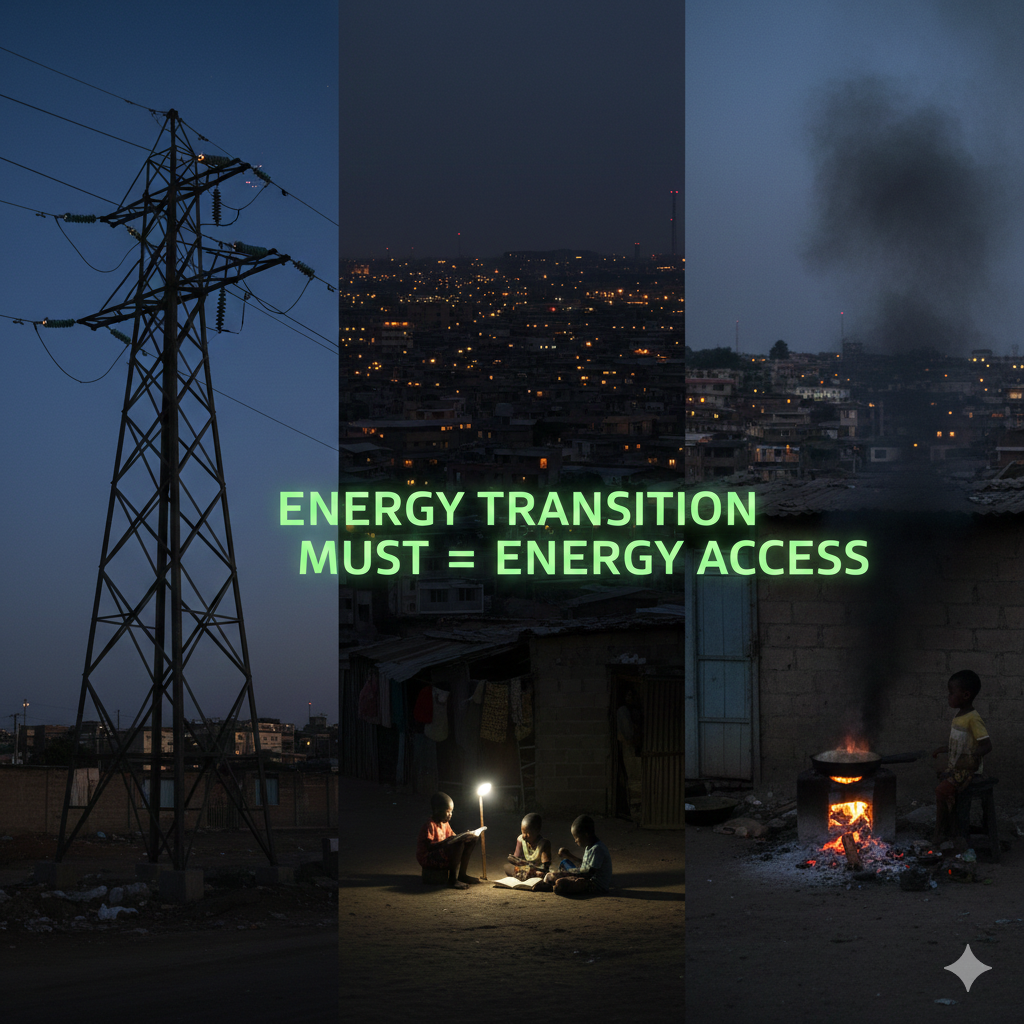

When a solar project is delayed in Europe, it is inconvenient.

When a solar project is delayed in rural Malawi, a clinic stays dark.

When a system fails in California, a warranty covers repairs.

When it fails in northern Nigeria, a family goes back to kerosene and to inhaling smoke every evening.

In wealthy countries, installers are scarce. In Africa, they are scarce and expected to be magicians, able to troubleshoot, wire, climb, diagnose, negotiate, repair and educate, all while operating in places where logistics and spare parts are luxuries.

Our solar boom is outrunning our ability to staff it.

This is the contradiction we rarely name: The continent with the most sunlight has the fewest people trained to harness it.

The causes are well known but rarely connected into a coherent picture:

Most training centres are in cities far from where solar installations are booming. And many courses are heavy on theory, light on practical work.

Solar companies report a troubling trend:

Train someone well, and they leave for a better-paying NGO job or migrate to the Gulf or Europe.

Africa is not just losing workers.

We’re losing experience.

Despite making up more than half the population, women form less than 20% of the renewable energy workforce. Our industry is missing an entire hemisphere of talent.

Development banks will pay for megawatts.

Governments will pay for infrastructure.

But funding for workforce development is an afterthought.

In many TVET institutions, students still learn electrical theory from the era before solar became mainstream. They graduate knowing circuits, not rooftops.

The result is a peculiar irony: Africa is rich in sunshine, rich in youth, rich in potential, but poor in the very skills we need to unlock it.

In rural Zambia, I met a mother who once received a small solar home system from an NGO. For six months, it worked beautifully. Her children studied at night. She cooked with less smoke. Her family spent less on kerosene.

Then the system failed.

The installer had relocated.

The local technician had switched sectors.

No one within 50 kilometres knew how to repair it.

Her words were simple, but devastating:

“We wait for the next NGO.”

That single sentence captures the tragedy of Africa’s solar skills crisis. Technology without talent is temporary. Light without maintenance is fleeting. Progress without people is fragile.

Yet this crisis is not only a warning, it is an opportunity that Africa has not fully recognised.

Solar is one of the few industries in the world that can:

If Africa invests in its solar workforce, the continent could create not just electricity but livelihoods. Not just installers but innovators. Not just energy but prosperity.

The solar transition is not simply a technological revolution. It is a people’s revolution.

But only if we choose to build the people who will lead it.

Not everyone can leave their village to study in a city.

Training must come to them.

Mobile labs, community-based centres, district-level partnerships, and training embedded in mini-grid deployments can close the distance between talent and opportunity.

Africa must replace scattered short courses with a full ecosystem:

A profession cannot be built on workshops alone.

Technicians leave because they are underpaid, under-recognised, and overworked.

Retention incentives, benefits, and long-term contracts must become the norm, not the exception.

Every solar investment should include a workforce investment.

Every donor programme should allocate a percentage to training.

Every government tender should require in-country skills transfer.

We cannot install our way into the future without the people who make installation possible.

The future African solar workforce must be female.

Not because of diversity goals, but because Africa cannot afford to ignore half its talent.

I often think back to that young technician in Nigeria, the one on the school rooftop, tightening bolts with a care born of purpose. He represents what Africa already has: courage, ingenuity, potential.

But he also represents what Africa risks losing if we do not act:

the skilled hands that can hold the sun.

Africa’s solar future will not be built by panels.

It will be built by people.

And the question before us, governments, funders, companies, and communities, is painfully simple:

Will we invest in the sunlight above us, or the talent among us?

The answer will determine not only whether the lights stay on, but whether Africa’s children inherit a continent capable of powering their dreams.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....