Too Many Panels, Too Little Value: Africa’s Solar Import Dilemma

For more than a decade, the global energy transition has been sold as a story of technology. We are told solar panels are getting cheaper, wind turbines are getting taller, and batteries are...

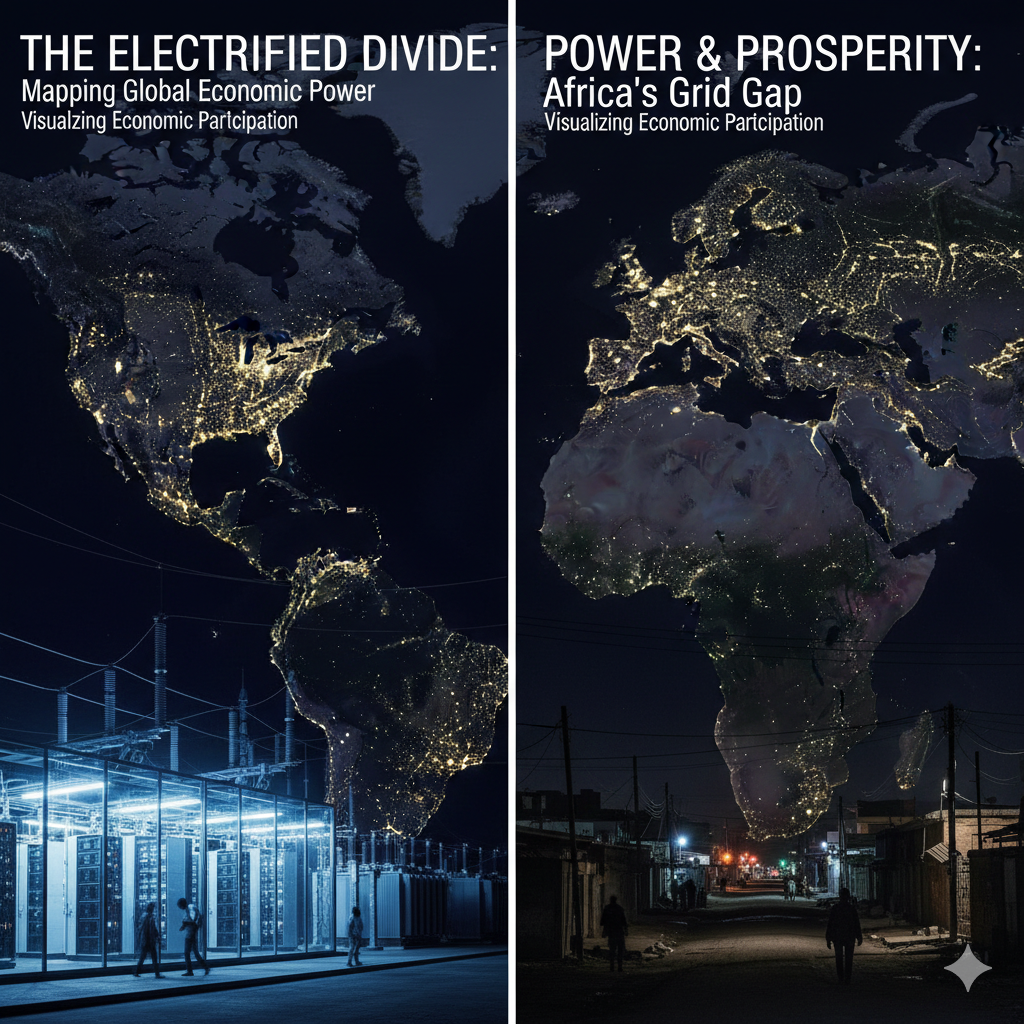

For most of modern economic history, electricity demand has followed growth. When economies expanded, electricity use rose steadily and predictably, rarely faster. That relationship is now breaking....

Almost everywhere you look across Africa, the sun is being harnessed, but not owned.

From the shimmering rooftops of Nairobi’s new tech hubs to the sprawling solar farms outside Lagos, it feels like the continent is finally catching the light. The World Bank estimates that solar capacity across Sub-Saharan Africa has tripled in the past five years. Panels glint across city estates, rural mini-grids, and corporate complexes. It’s a visible revolution, but beneath that glare lies a quiet dependency.

Because almost every one of those panels was imported.

When I first visited a community solar installation in northern Nigeria earlier this year, the pride was palpable. The women’s cooperative had finally powered their grain mill; the children could now study under clean light. But all those panels and batteries were imported, mostly from China. And this is the same thing you'd find across the continent.

According to Energy-News Network’s 2025 data, Africa imported over $4.7 billion worth of solar panels and components in the past year alone, a 39 percent jump from 2023. Yet less than 2 percent of these panels were manufactured or assembled on the continent. The surge in imports is both progress and a warning: while it signals rising demand for clean energy, it also exposes how little of that value is captured locally.

Every panel that arrives through African ports carries within it the labour, technology, and profits of another economy.

The truth is, Africa’s solar boom is globalisation in reverse. We consume the technology; others produce the wealth.

China currently controls about 80 percent of the world’s photovoltaic manufacturing, from polysilicon refining to module assembly. The European Union, India, and the United States dominate the high-value engineering, logistics, and finance. Africa’s role? Mostly an importer and installer.

This asymmetry is not new; it’s the same model that defined the fossil era. We exported crude oil and imported refined petrol. Now we export lithium, cobalt, and manganese, and import finished batteries, panels, and turbines. The language has changed, but the economics remain painfully familiar.

The idea of producing solar panels locally has long been a policy dream. Countries like South Africa, Egypt, and Morocco have made partial headway, yet structural barriers persist.

The result is predictable; local factories cannot compete on cost or scale. South Africa’s few solar assembly lines have struggled to survive without government protection, while Nigeria’s fledgling firms face unreliable power and erratic foreign exchange access.

This dependency traps Africa in the “installer economy”, the final mile of a global supply chain designed elsewhere.

At first glance, imported panels seem harmless. After all, clean energy is better than no energy. But the hidden cost lies in economic sovereignty.

Our energy transition is being financed in foreign currencies, executed by foreign companies, and built with foreign technology. When currencies weaken or global supply chains tighten, as seen during the pandemic, the entire clean-energy pipeline trembles.

A recent report by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) warned that over-reliance on imports exposes African energy markets to currency volatility and supply shocks. It also perpetuates the narrative that Africa’s energy future must always depend on external expertise.

It’s the same logic that once justified decades of fossil fuel dependency, only now, the fuel is sunlight.

There’s a better way forward, and it starts with value addition.

Instead of competing with China on full-scale module production, Africa can carve out strategic niches: glass manufacturing, aluminium framing, battery assembly, and inverter electronics. These are lower-entry-barrier components that can anchor local supply chains.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) provides an opportunity to integrate markets and build regional manufacturing clusters. A solar-panel glass plant in Egypt could serve the North African corridor, while a battery assembly line in Kenya or Ghana could supply East and West African grids.

Equally important is developing the skills and intellectual property that accompany technology. Africa must move from merely adopting renewable solutions to designing them, through stronger R&D ecosystems, local engineering hubs, and vocational training tied to green industries.

We have been here before. In the 1970s, industrialisation plans tied to imported machinery collapsed under debt and currency crises. The lesson is that import-led growth without local reinvestment creates fragility, not resilience.

Today’s solar import boom risks repeating that history. The continent’s renewable revolution could either ignite a wave of local innovation or become another export market for global manufacturers.

The difference lies in policy courage: whether governments will move from procurement to production, from consumption to creation.

One crucial piece of the puzzle is finance. Most solar investments are funded through euro- or dollar-denominated loans, exposing developers to exchange-rate risk. A project financed at nine hundred naira to the dollar becomes unsustainable if the rate slips to one thousand four hundred naira.

Local-currency financing, facilitated by African development banks, can de-risk renewable investments and keep profits circulating domestically. Institutions like Afreximbank, DBSA, and the African Development Bank could pioneer green-bond instruments that fund solar manufacturing zones and innovation hubs.

This shift would transform solar power from an import expense into a domestic growth driver.

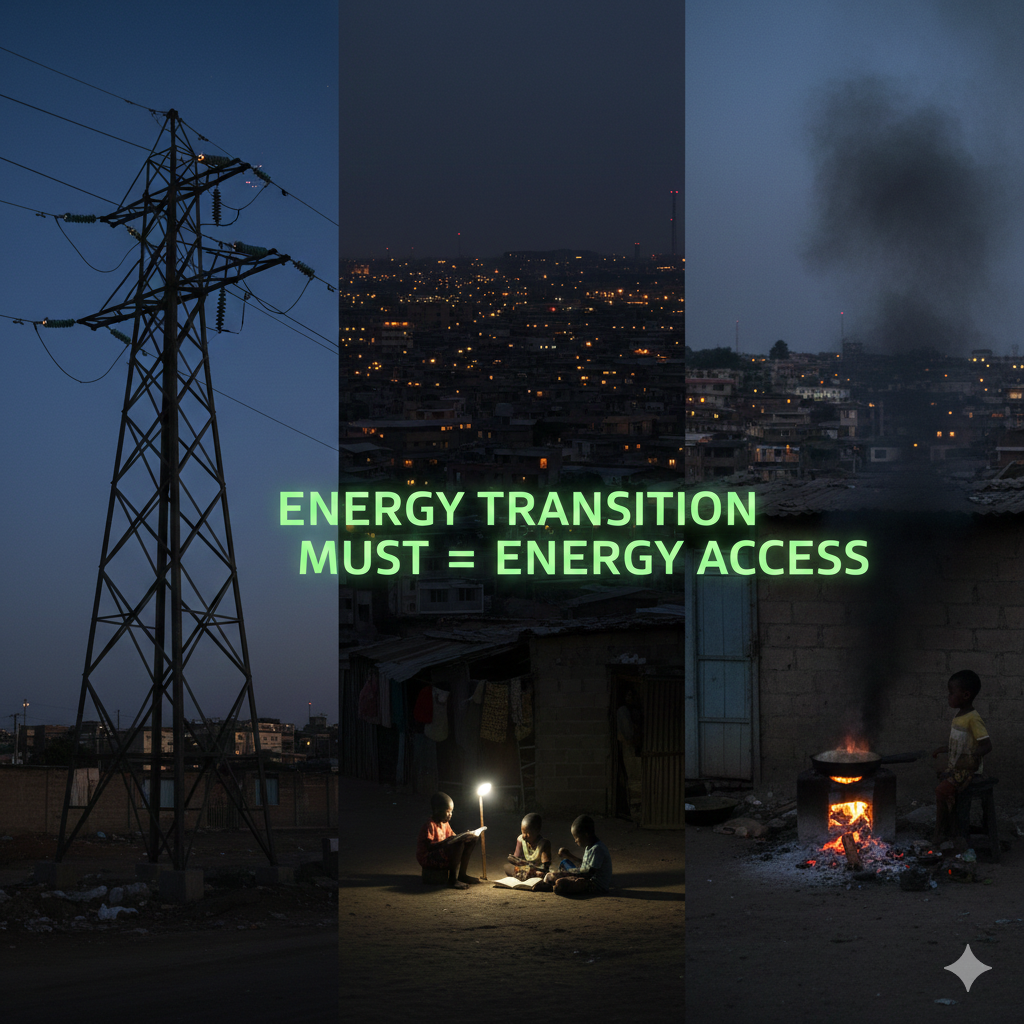

Energy justice is not only about connecting homes to power; it’s about connecting economies to opportunity.

When we talk about Africa’s energy transition, we often celebrate access, the number of people electrified, or the megawatts installed. But the deeper question is ownership: Who makes the technology? Who finances it? Who profits from it?

The current solar boom shows that Africa can light up its cities and remain in the dark economically. To change that, every installation must also plant the seeds of industry, training, manufacturing, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

Because energy sovereignty isn’t achieved by importing panels. It’s built, piece by piece, by those who make them.

If we continue importing 98 percent of our solar technology, the continent’s green revolution will shine brightly but briefly, owned elsewhere, controlled elsewhere, and taxed elsewhere.

But if our governments can coordinate industrial policies, build regional manufacturing, and finance innovation locally, the solar economy could become the continent’s next great leap.

The sun that powers Africa’s homes must also power its factories.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....