Africa’s Energy Crisis Is Killing People. Here’s the Data Behind the Emergency

For much of Africa, the diesel generator has become an unspoken pillar of the economy. It powers factories when the grid fails, keeps hospitals running during blackouts, and underwrites commercial...

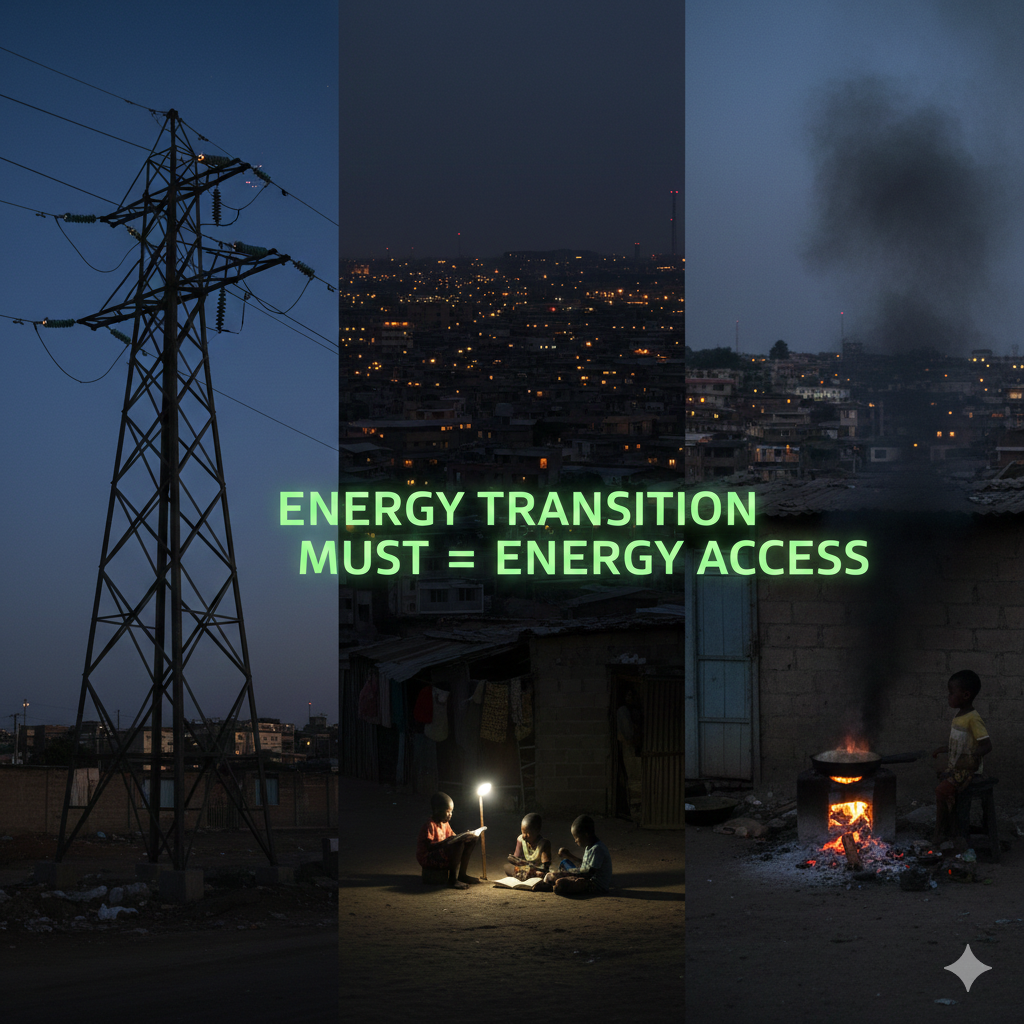

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....

Some crises announce themselves loudly, while others unfold quietly, suffocating people long before the world names them. Africa’s energy crisis belongs to the latter. It is spoken of in terms of infrastructure, investment gaps, and megawatt targets, but at its core, this crisis is fundamentally a matter of life and death.

The continent’s chronic energy poverty is not merely an economic barrier. It is a public health emergency of staggering scale, claiming millions of lives, weakening health systems, deepening gender inequality and limiting human potential before it even begins to grow. The statistics are numbing in their repetition, but the human cost is fresh every day.

The absence of electricity, clean cooking, and reliable power is undermining Africa’s ability to survive, not just develop. And unless policymakers reframe energy access as an urgent health intervention, not only a development goal, the continent will continue to lose lives that were entirely preventable.

According to the World Health Organisation, 2.3 million people die every year from illnesses linked to household air pollution, with Africa accounting for the majority of these deaths. The cause is brutally simple: 900 million Africans still cook with charcoal, firewood, or dung, releasing toxic smoke that damages lungs, weakens immune systems and increases the risk of pneumonia, heart disease and chronic respiratory conditions.

In many African households, cooking a meal requires inhaling the equivalent of smoking two to ten cigarette packs a day. Babies strapped to their mothers’ backs breathe the same smoke; studies have shown that newborn exposure increases the likelihood of stunting, low birth weight, and long-term cognitive impairment.

The consequences fall disproportionately on women. According to UN Women, African women spend over 200 hours each year collecting fuel, time taken from education, income generation, rest, and dignity. Clean cooking is not merely an energy upgrade; it is a pathway to gender equality and better health outcomes.

Yet despite decades of warnings, progress remains painfully slow. Clean cooking receives less than 1% of global energy finance, a paradox when its health benefits rival some of the largest public health interventions of the last century.

Energy poverty is equally devastating within Africa’s health facilities. New analysis from Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL) and the World Bank shows that 60% of health clinics in sub-Saharan Africa lack reliable electricity, and nearly a quarter have no electricity access at all.

This means:

In facilities without electricity, maternal mortality rates are three times higher. Newborn mortality rises sharply when incubators and radiant warmers cannot operate. In many rural clinics, surgeons rely on phone torches when backup generators fail. This is not a metaphor; it is a daily reality.

Electricity is not a luxury for health systems; it is their foundation.

If Africa is to have resilient healthcare, it must first have reliable power.

hildren bear the highest cost of Africa’s energy shortfall. Pneumonia, primarily driven by air pollution, remains among the leading killers of children under five on the continent. UNICEF warns that vaccine spoilage rates remain unacceptably high because 40% of rural health facilities cannot keep medicines consistently refrigerated.

And at home, millions of children study under kerosene lamps, candlelight or phone torches, increasing risks of burns, poisoning and respiratory illness.

Energy poverty harms a child’s lungs, brain, education, safety, productivity, and life expectancy, a cradle-to-adulthood assault. It is a generational health crisis that quietly determines who survives and who does not.

This is why in a previous article, we argued that Africa’s clean-energy transition must prioritise households and health facilities before heavy industry.

Electricity enables life and not merely economic growth.

For decades, African governments and global institutions have evaluated energy access through the lens of infrastructure. How many megawatts were added? How many kilometres of transmission lines were built? How many households received first-time grid access?

But when energy is seen through a health lens, the questions change.

Suddenly the focus shifts to:

This reframing matters because it aligns energy with Africa’s political priorities: child survival, universal healthcare, gender equality, productivity, and human capital.

Energy is not a sectoral issue; it is the bloodstream of public health.

Therefore, the next decade must prioritise four urgent interventions.The continent cannot achieve SDG3 (good health) without achieving SDG7 (energy access).

SEforALL estimates that electrifying all health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa is feasible within five years using a combination of grid upgrades, mini-grids, and solar + battery systems.

This should be non-negotiable. No mother should die because a clinic is dark.

Africa loses more lives to household air pollution than to HIV, malaria and tuberculosis combined.

And yet, financing remains microscopic.

Governments must adopt clean-cooking transition plans, create incentives for LPG, electric cooking, ethanol, and improved biomass technologies, and integrate these solutions into health policy.

Energy + Health = Survival.

Mini-grids, solar home systems and standalone power for clinics offer the fastest route to saving lives. Many rural regions will not receive grid access soon enough.

We have consistently argued that decentralised energy is a health solution, not merely an energy one.

Ministries of Health should track:

What is not measured cannot be saved.

Africa’s energy crisis is not a 2050 problem. It is a right-now emergency affecting every clinic, school, mother and newborn. A continent that is central to the world’s clean-energy transition cannot remain in the dark at home.

The data is undeniable. The human cost is unbearable. The time for treating energy as a “development target” has passed.

Africa must treat energy as the lifesaving public health intervention it is.

Because light is not just a service.

It is survival.

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

For years, the global energy transition has been narrated as a linear story: renewables rise, fossil fuels fall, and gas fades as a temporary bridge. That story is now colliding with reality. In late...