Dig, Ship, Repeat? The Extractivist Trap in Africa’s Critical Minerals Boom

For more than a decade, the global energy transition has been sold as a story of technology. We are told solar panels are getting cheaper, wind turbines are getting taller, and batteries are...

For most of modern economic history, electricity demand has followed growth. When economies expanded, electricity use rose steadily and predictably, rarely faster. That relationship is now breaking....

Walk into any electric vehicle showroom in Berlin, Los Angeles or Shanghai, and you are looking at Africa. The cobalt that steadies the battery, the copper that carries the current, and the manganese that strengthens the cathode are dug from African soil. The continent has become the unspoken backbone of the global energy transition.

Yet history casts a long shadow. For centuries, Africa’s raw materials have powered other continents, leaving little wealth at home. Palm oil, gold, rubber, copper, oil, etc, the story was often the same: dig, ship, repeat. Now, in the age of climate urgency, the same trap is opening around critical minerals. Unless governance changes, Africa’s minerals will once again be exported cheaply, while the real value, the batteries, the cars, and technology, is imported back at a premium.

This is the central irony of the clean energy revolution: the drive to build a greener world could lock Africa into another dirty past.

What makes this trap particularly insidious is governance. In many mining agreements, companies secure stabilisation clauses that freeze tax rates, royalties, and regulatory conditions for decades. While this provides investors with certainty, it chains African treasuries to deals that remain static while global prices fluctuate.

When copper or cobalt prices surge, governments cannot raise royalties to reflect the windfall. When environmental standards evolve, reforms are stymied by the fear of arbitration. Consider the DRC, which supplies more than 70% of the world’s cobalt. Even with soaring demand, revenues remain disproportionately low. Why? Because contract structures written years ago continue to dictate today’s returns.

“If climate urgency drives up demand for lithium, why should Africa’s revenues stay frozen in time?”

Critical minerals are being hailed as the new oil. But the comparison cuts both ways. Oil once promised transformation in Nigeria, Angola and Equatorial Guinea. It delivered some revenues, yes, but also corruption, environmental devastation, and Dutch disease. Jobs are scarce, economies distorted, and communities left in poverty.

Now, lithium, cobalt and manganese risk becoming the “new oil curse”. Mining towns are already seeing familiar patterns: environmental degradation, unsafe artisanal mining, and elite capture of revenues. In Kolwezi, children toil in hazardous pits, even as Tesla’s market capitalisation surpasses the GDP of entire African states.

The danger is stark: Africa could remain the quarry while others assemble the future. The narrative becomes another century of dig, ship, repeat, minerals out, finished technology in.

Timing is everything. The International Energy Agency forecasts that demand for lithium could grow fivefold by 2040; cobalt demand is expected to double. Battery metals are becoming the most strategic commodities of the 21st century. Whoever controls supply chains controls the future of mobility, storage and power.

China has understood this. It dominates Africa’s mining sector, not only through investment in extraction but also by controlling refining capacity. The EU and US, through their Critical Minerals Acts, are scrambling to secure supply lines but largely exclude African processing. Without a continental response, Africa will again be the supplier of ores, not of opportunity.

The human cost of extraction often goes missing in policy discussions. In Guinea’s bauxite belt, communities live with dust-choked air and broken infrastructure while bauxite ships depart for China. In Zimbabwe, lithium mines have displaced farming families with little compensation. In Zambia, copper revenues flow, but schools and clinics remain underfunded.

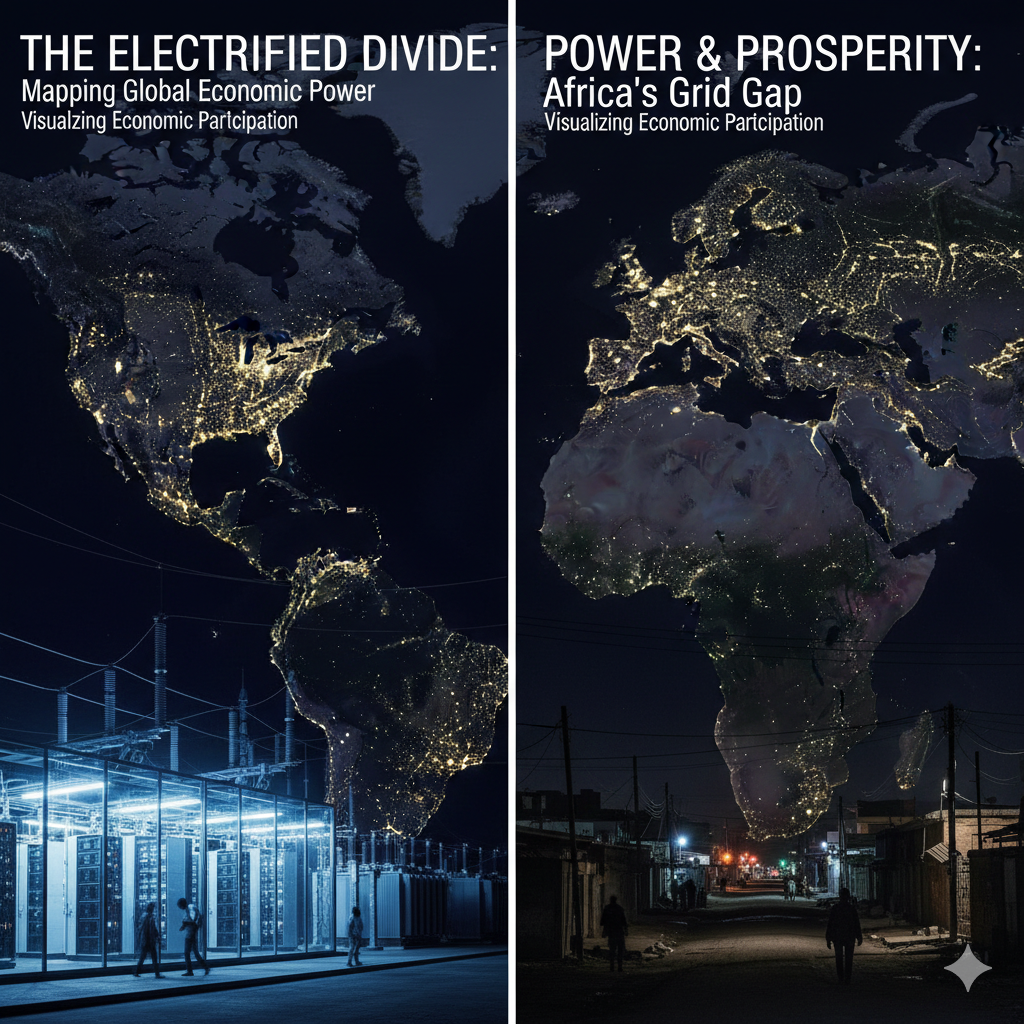

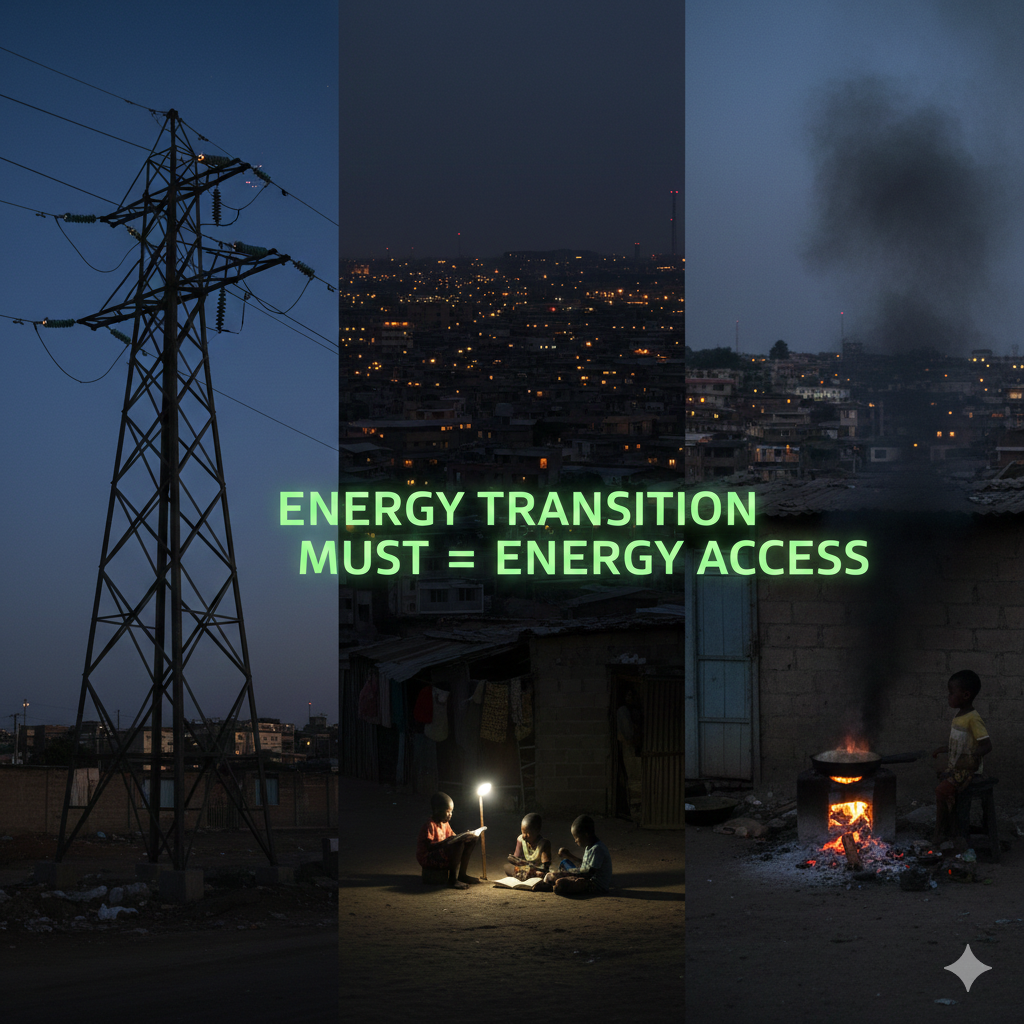

This is the bitter paradox: Africa digs the minerals that light up Teslas in California and batteries in Europe, but many mining towns remain literally in the dark. For the people living alongside the mines, “just transition” is a distant phrase. Their reality is unpaved roads, polluted rivers, and promises that seldom reach.

“Africa digs, the world drives Teslas, but mining towns stay in the dark.”

To break the cycle, Africa must shift from extraction to transformation. That means industrialisation through value addition. Three pathways stand out:

Industrialisation is not enough; governance must evolve. Transparency in contracts, community revenue sharing, and gender-inclusive participation are essential. Civil society networks like Publish What You Pay are already pushing for contract disclosure and stronger regulatory regimes.

The challenge is political will. In too many capitals, mining revenues remain opaque and captured by elites. Without accountability, even beneficiation, risks becoming another elite rent-seeking scheme. The transition must be not only green but just, a governance revolution as much as an industrial one.

The climate summit will be a critical stage. Here is what African negotiators should put on the table:

This is not protectionism; rather, it is justice. If the world needs Africa’s minerals for a clean transition, it must pay fair value and support Africa’s climb up the ladder.

Africa stands at a crossroads. Critical minerals could be the foundation of a new industrial age, or the chains of a new extractive cycle. The difference will be governance and making the right decisions.

The choice is between dig, ship, repeat, a century-old pattern or mine, refine, prosper, a future where Africa owns a share of the green economy it sustains.

“The question is not whether Africa will mine. It’s whether Africa will mine and rise, or just mine and repeat.”

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against....