Africa’s Climate Finance Crisis: The Debt Trap Undermining a Greener Future

For more than a decade, the global energy transition has been sold as a story of technology. We are told solar panels are getting cheaper, wind turbines are getting taller, and batteries are...

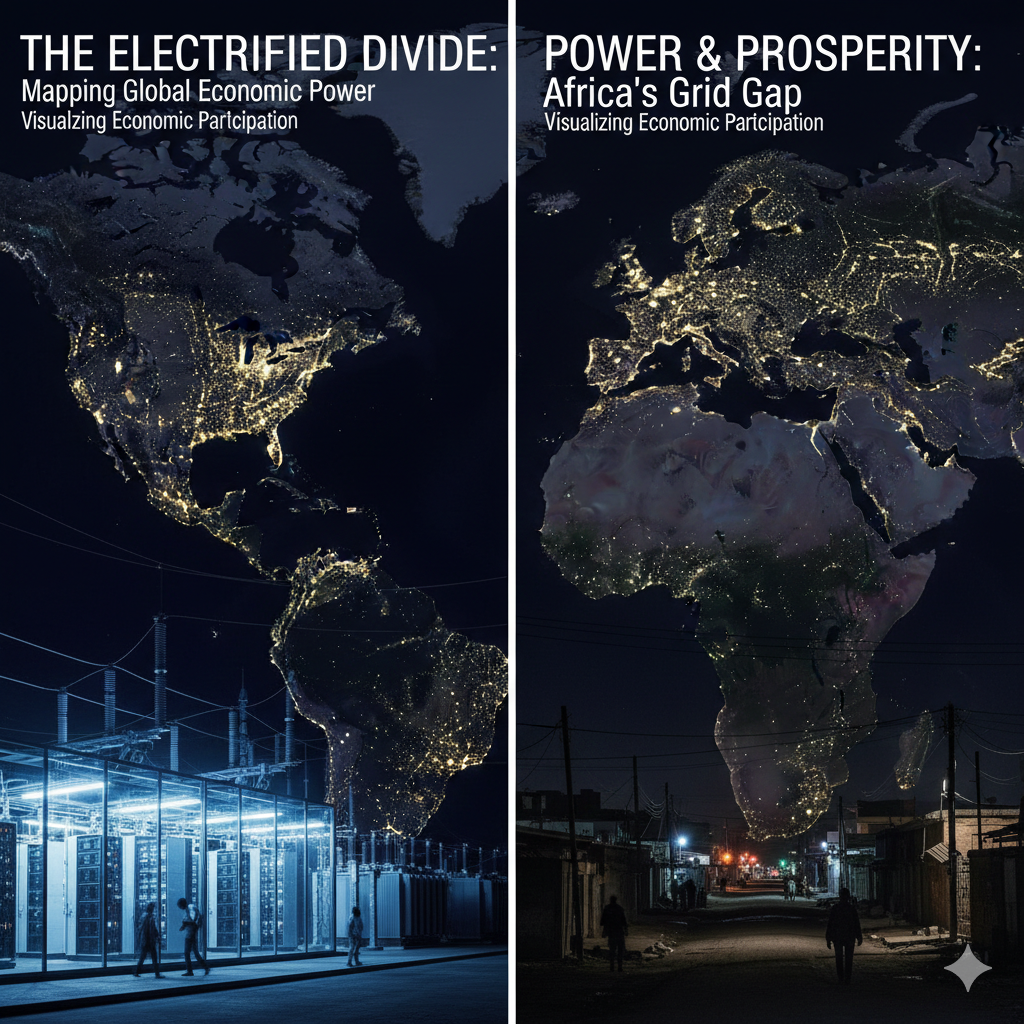

For most of modern economic history, electricity demand has followed growth. When economies expanded, electricity use rose steadily and predictably, rarely faster. That relationship is now breaking....

In the heart of Africa, a paradox unfolds. A continent so rich in renewable resources, from sun to wind and lithium to cobalt, is simultaneously suffocating under the weight of financial obligations it did not choose but must now navigate. At the centre of this tension lies climate finance, the tool meant to support energy transitions but one that, for many African nations, increasingly feels like another shackle.

According to the Climate Policy Initiative’s 2024 Africa Climate Finance Landscape report, Africa received approximately $43.7 billion in climate finance flows during 2021–2022. While that figure marks a 47% increase from 2019/2020, it remains far short of what is required. The African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates the continent needs up to $174 billion annually to meet its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement.

Yet, the devil is in the detail. More than 51% of that finance is debt-based, split between concessional loans (34%) and market-rate loans (17%). For countries already struggling with debt distress, this pushes them closer to fiscal collapse.

In a June 2024 study, the Institute for Economic Justice warned that by 2030, African nations will be spending 137.4% of their annual climate financing needs just on servicing public debt. This means the same budgets meant to support clean energy infrastructure, education, or health systems are being drained to pay off international lenders, many of whom hail from countries with the largest carbon footprints.

The situation becomes even more fragile when compounded by inflation, currency devaluation, and rising interest rates. According to Moody’s, only a few African countries like Benin and Côte d'Ivoire have taken steps to shield themselves by expanding local debt markets. The rest remain highly exposed.

The Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) with South Africa was supposed to be a beacon example. Launched at COP26, it promised $8.5 billion in funding to help South Africa move away from coal dependency. But fast-forward to 2025, and the partnership is fraying.

The recent withdrawal of the United States from its commitment of $1.56 billion has rattled confidence in the deal and exposed the fragility of multilateral energy transition commitments. Even though the EU, UK, Germany, and France have pledged to carry on, civil society observers say the damage has been done.

According to a joint statement from the International Partners Group, more than $2.5 billion has already been disbursed. But the majority is still structured as loans, many of which come with conditions that critics say could undermine sovereignty and social equity.

Another glaring issue is the unequal distribution of climate finance. The top 10 recipient countries received 46% of total flows, while the 10 most climate-vulnerable countries secured just 11%, according to the Climate Policy Initiative.

This mismatch between vulnerability and access raises critical questions. Countries like Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Niger, some of the poorest and most climate-exposed, struggle to attract the finance they need. Meanwhile, more politically stable or resource-rich countries receive larger shares, even when their emissions profiles or climate risks are lower.

This points to a larger flaw in the global finance system: it rewards the bankable, not the vulnerable.

In this landscape, African civil society must rise as both a watchdog and a conscience. Organisations across the continent are already:

As argued by the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), the G20 can no longer afford to speak in vague terms about “support” while avoiding decisive action. The continent's civil society now needs seats at the table, not just observer status.

The African Group of Negotiators on Climate Change (AGN) has been clear in its stance. At COP meetings, they have consistently advocated for the establishment of a Loss and Damage Fund and for reforming institutions like the World Bank and IMF to better reflect the realities of the Global South.

As long as climate finance remains fragmented, conditional, and debt-heavy, the just transition will remain a slogan, not a solution.

Despite these challenges, hope remains.

Africa has what the world needs: sunshine, wind, youth, and critical minerals. But to move from potential to power, the continent needs a financing ecosystem that works for it, not against it. Blended finance, debt relief, climate risk insurance, and community-based adaptation models are all being tested.

And with the right global will, Africa’s path to a clean energy future could set the pace for the rest of the world.

Africa's climate finance crisis is not just about numbers. It's about justice, equity, and survival. If the world truly believes in climate action, then supporting Africa's energy transition is not an act of charity, it is a shared responsibility.

The time for words is over. What Africa needs is money on the table, trust in the process, and freedom from debt that has outlived its usefulness.

For more stories on Africa’s energy transition and civil society voices, visit EnergyTransitionAfrica.com

Contributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.

As Mining Indaba opens in a few days, one point of alignment is already clear: value addition has become the dominant political language around Africa’s future in critical minerals. From policy...